A Tale of Two Dereks: The Chauvin Trial and American History X - Issue #27

Derek Chauvin's defense strategies are oddly reminiscent of one of the most problematic films of the 90s.

When American History X (Tony Kaye 1998) was released, it was hailed in many quarters as a visionary exploration of the psychological mechanisms of racism and the violence that inevitably emerges from it. Have a look at the aggregated reviews on a site like Movie Review Query Engine (my film criticism clearinghouse of choice), and you’ll find a phalanx of glowing “4.5 out of 5 Stars” reviews praising its unflinching assessment of white supremacy’s poisonous allure to disaffected young men, its depiction of a family in crisis, and its (admittedly) stellar acting.

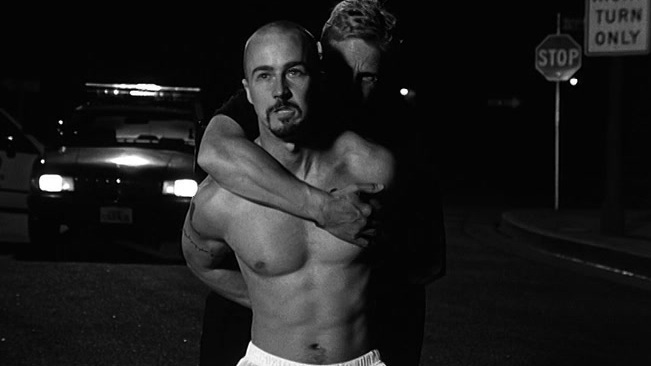

A mainstream movie—featuring a super-buff Edward Norton, the kid from Terminator 2 (Edward Furlong), Commander Sisko from Deep Space 9 (Avery Brooks), both the dad and the chunky kid from Boy Meets World (William Russ and Ethan Suplee), and, incongruously enough, Ross and Monica’s father from Friends (Eliot Gould)—that dramatizes a dystopian post-Rodney King Los Angeles, and gives its charismatic lead a cathartic redemption arc from volatile-but-eloquent skinhead to conflicted social justice advocate?

A concluding scene that aspires to Shakespearean-caliber ironic tragedy?

A slick marketing campaign, bolstered by word-of-mouth enthusiasm, that promoted it as THE movie about the toxicity of bigotry?

It was bound to be a mainstream cult hit, to be regarded as possessing the same sort of cultural heft as, say, David Fincher’s Seven: both are garish, unapologetically violent films that purport to communicate central truths about society and human nature, and that end on a note that ominously embraces optimism and pessimism in roughly equal measure.

I watched it early in my freshman year of college, and was easily seduced by it. For years, I told people it was “brilliant.”

It’s not.

As Rob Gonsalves, one of the few critics who caught onto the bankruptcy of the film’s moral vision from the beginning, puts it: “American History X is trite rubbish— an ABC Afterschool Special pumped up with flashy, pretentious style and ‘gritty’ realism.”

I’m not sure I’d go so far as to agree that it’s “rubbish”; it’s deeply and viscerally affecting, and any film that can achieve that is doing something right. But I can think of no other example of a movie that feels so starkly different upon rewatching.

It has its cheaply satisfying moments: the protagonist, Derek Vinyard (Norton) beating the shit out of an imperious white supremacist Godfather-type figure (Stacey Keach) after uttering the laughable tough-guy line “If you come near my family, I will feed you your fucking heart”; the younger brother, Danny (Edward Furlong), abandoning his racist views with zero reflection or hesitancy when the plot needs him to; Derek bonding with a black prisoner who, in turn, ensures that he is left alone by the other black inmates; these seemed to me in 1999 like Serious and Important Moments and, in 2021, as utterly asinine.

But it’s the dimestore provocations that really rankle: the infamous curbstomp scene (proceed with caution and, for the love of God, don’t read the comments); neo-Nazis engaging in prison rape (which is the primary reason Derek turns his back on the ideology, rather than the fact that the ideology itself is repulsive); so many casual racial slurs that it feels gratuitous, even in a film populated by proto-alt-right bigots.

Swastikas and Roman salutes and Iron Crosses and staid portraits of Hitler all over the place? Oh, you betcha.

But perhaps most damning, the film provides an arsenal of militant racist talking points that the narrative then tries to disown with little more than Derek covering up one of his Nazi tattoos while looking contemplatively into a mirror, and with Danny’s robotically-delivered line: “Hate is baggage. Life’s too short to be pissed off all the time.” Too little, too late.

In other words, a film that suspiciously spends much of its running time parroting the very lines of thinking that make racism appealing to the weak-minded and aggrieved, and stages sequences of gleeful violence against people of color, tries to take it all back and claim the opposite through a bit of dialogue that focuses not on the victims of racism, but on the emotional state of the racist himself.

For all of his populist bluster, Derek only becomes a neo-Nazi because his father is killed by a black man. He only disavows his ideology when he is assaulted by fellow neo-Nazis in prison. His relationship to racist (or, sort of, halfheartedly anti-racist) ideology is informed purely by how these things affect him and his interests; not others, not society.

It’s a film that wants to be important, but is unwilling to do much more than bombard its viewer with romanticized signifiers of hatred and eloquent justifications for beating up immigrants, and then lazily declare, in the third act, that Nah, actually, all that stuff is bad, got it?

Why, my readers might be wondering, have I devoted almost 700 words to attacking the pretensions of a more-than-two-decades-old film? A film that, despite all of my criticism, I believe likely had (poorly-executed) good intentions?

The movie resonates 23 years later as an encapsulation of the legal defense strategies of an arguably more monstrous Derek: former police officer Chauvin, the Minneapolis cop whose killing of George Floyd, captured on video in agonizing detail, ignited the most visible and consequential racial justice movement since the mid-1960s.

As I’ve already argued, American History X does the bare minimum to disown its rhetoric. But much of that rhetoric—which many critics hailed as uncompromisingly bold—is, in itself, based on mere objective observation. At one point, Derek riles up a gang of burgeoning white nationalists by pointing out that a local grocery store, one that several of his friends used to work at, is now owned and staffed by immigrants, a statement that is articulated as simple, indisputable truth. It’s the preexisting bigotry and aggrieved rage of the gang members that turns that statement into violence.

Chauvin’s attorney, Eric Nelson, relies on a similar phenomenon. He knows there are people who long for a reason to give Chauvin the benefit of the doubt. History has shown that America is very willing to forgive police brutality when given a plausible opportunity. By positing that “the evidence is far greater than nine minutes and 29 seconds,” by suggesting that we ought to look beyond the horrors that were captured on video and apply “common sense,” Nelson is really asking us to apply our own anecdotal experiences to our perception of the case, to feel free to allow our own subjective biases to distort the plain-to-see thing that unfolded on May 25.

There most assuredly exists a mentality, after all, for which simply pointing out, accurately, that “there was a restless group of (mostly) Black people yelling at Chauvin” easily translates into Derek Chauvin was in danger and can’t be blamed for using too much force, just as pointing out that an awful lot of non-white day laborers seem to hang out in front of the Home Depot—an undeniable phenomenon in some American cities—can effortlessly translate into Immigrants are taking all of our jobs. Or claiming that a 12-year-old boy playing with a toy gun “looked older and bigger” can be leveraged into Well, you can’t blame the cop for shooting him.

Seemingly objective observation, coupled with preexisting biases and the need to excuse violent white men, curdles easily into reactionary and racist action.

Nelson’s narrative is also the sort that inevitably appeals to those who promote the “Blue Lives Matter” ideology, an ideology whose name is a shameless appropriation, and a condescending rebuke, of Black Lives Matter, and which claims to disapprove of racism and discriminatory policing methods, while simultaneously insisting that the existence of those very things is grossly exaggerated, despite the evidence offered in study after study after study.

In other words, credulity toward Chauvin’s lawyers’ arguments is not the exclusive domain of the sort of virulent bigots that populate right-wing message boards and plan terroristic assaults. I am not referring here to people who are either hateful or deluded enough to claim that Floyd’s death was entirely his own fault, or that Chauvin is perfectly innocent, or even that Floyd’s checkered history is enough to decide that his death was actually a good thing. Such perspectives do exist, and you can find them easily if you are masochistic enough to venture into a Fox News comment section. Such people, those who wear their bigotry on their sleeves, are beyond decency and reason, and not worth engaging with.

But those whose worldview is targeted by the defense team’s strategies—insisting that the pressure-cooker of stress that constitutes police work justifies giving Chauvin the benefit of the doubt, and appealing to perennial myths about Black men, crime, opioid use, and violence—would, for the most part, be genuinely aghast at the idea that anyone might think of them as prejudiced. They are, notably, also unlikely to accept that racism is largely defined by unconscious bias and systemic, not personal or individual, experiences.

The vast majority of Americans (even those who spent much of the summer clutching pearls over the resulting protests) agree that Floyd’s murder was inexcusable if not horrific. However, there is still a significant contingent insisting upon a narrative that, while not necessarily exonerating Chauvin, purports to “add context” or “look at things rationally,” to counteract the prosecution’s and the media’s alleged overreliance on emotion. It is unsurprising that his defense team is offering up such a gambit—defending the indefensible is literally their job right now—but it is somehow at once shocking and utterly predictable that so many Americans are willing to buy into it.

Such is the outcome of a semi-mainstream “bothsidesing” perspective, the result of American media consumers who are wary of Black Lives Matter’s ascendancy and who tends to lament that “Everything is about race these days”; worldviews shaped by arguments that, for instance, a host of extenuating factors essentially forced Chauvin to act inappropriately. Or, even more preposterously, that Floyd just happened to overdose during the same period of time in which Chauvin’s knee was crushing his neck.

I doubt that this strategy will get Chauvin acquitted. But what it will do is reinforce within the popular consciousness idealizations about race and policing that continue to obstruct badly-needed reforms and reformulations concerning law enforcement’s role in society.

Those who find plausibility in Chauvin’s anemic litany of reasons for acquittal display a susceptibility to the kind of rhetoric that suffuses American History X: vestiges of bigotry exploited by a cynical veneer of “Hey, this is just common sense!”

Chauvin’s defense insists that there is some “real truth” hidden beneath the damning video evidence, a truth rooted in rational logic that our emotional reactions to that video are not allowing us to see. This, of course, is the go-to rhetoric of the conspiracy theorist, something to the effect of: Don’t be like all those sheep and conformists who believe the “official story”! Show that you are an independent thinker by giving credence to this (highly dubious) alternative narrative!

These lines of thinking are, by design, a gish gallop of cynicism and paranoia and dilettantism dressed up as rigorous and iconoclastic intellectualism. As we have seen over the past several years, it’s an irresistible M.O. for some of the most abhorrent sociopolitical positions imaginable, whether the Stop the Steal movement or the “Plandemic” video that made the rounds last May or, as I’ve written about elsewhere, the baffling belief that wearing a mask is a capitulation to tyranny. In this case, it gives the public a way to believe in and defend Chauvin while still disavowing injustice in policing generally—but, again, by also disavowing, or at least egregiously minimizing, that racism in policing and society even exists.

Chauvin’s legal team and some of his more vocal supporters pull a similar move to American History X’s meek disowning of the very mentality it has gratuitously promoted. They will gladly offer a rote, obligatory note of sorrow for Floyd’s death, preposterously claim that the trial ought to be treated as devoid of racial and culture war subtexts (“There is no political or social cause in this courtroom,” Nelson absurdly declared last week) . . . and then launch into a relentless dogwhistling campaign brimming with racial and culture war subtexts.

Similarly, for all of its self-congratulatory third-act messaging about the wrongness of hateful ideologies, American History X uniformly portrays Black and Latinx people either as one-dimensional gangbangers or as nominally positive, but stalely reductive, stereotypes. As Gonsalves puts it in his review concerning the latter, these characters “[seem] to exist only to deflect possible charges that the movie itself is racist.”

It’s the cinematic equivalent of saying I’m not racist but . . . and then musing that maybe George Floyd bears some responsibility for his own death.

Or uttering some misinformed remark about violence in inner-city Chicago.

Or claiming that a 12-year-old playing at a park was “in the wrong” and culpable for his own shooting death.

Or arguing that Breonna Taylor got what was coming to her because she dated someone who might have been involved in drug-dealing.

Or wondering why you’re “not allowed to use the N-word” when Black people supposedly do it all the time

Or mocking the grief (and the language used to express that grief) of victims’ families.

Or hundreds of other verbal aggressions in which theoretically-innocuous observations are transmogrified into a portrayal people of color as inherently violent, and as responsible for violence committed against them.

In both the film and the trial, a limp gesture toward righteousness and justice—offered essentially as an afterthought—is a grotesquely insufficient corrective to the romanticization not only of injustice, but of the pseudo-intellectualized appeals to personal bigotry that underpin it.

The ideas expressed above are solely those of the author.