When you look back at your life, can you pinpoint particular people or events that had an outsized influence on who you’ve become, that shaped you in ways that still resonate? The movie Inside Out, which I love, calls these core memories.

I want to start listing, but there are too many, and the list will be incomplete. We don’t hold all these memories at the forefront of our minds at all times; that would be exhausting. Rather, it’s interesting how they come up occasionally—called forth from the deep recesses of memory, sometimes triggered by something, sometimes seemingly at random.

Here’s one. I’m in my first year of college—at Gordon—sitting in a chapel, half paying attention. I don’t remember many chapel services (we were required to go three times a week), but this one has stayed with me. The theme for the semester was “Who is my neighbor?” and each week we were joined by a different neighbor—a local figure from the North Shore. I remember just this one, and just barely.

She was a minister and, she told us, lesbian. She had my full attention. That is until, I heard a door slam loudly as several students marched angrily out of the sanctuary. As I recall, the minister just went on with her talk—it didn’t seem like this was the first time something like that had happened to her.

But I was angry. I did what I always did when I experienced big emotions in those days, I wrote a poem about it. More importantly, I resolved at 18 years old to not be like those people who were so threatened by the existence of another person that they couldn’t even listen to her speak, that they had to make a show of their displeasure.

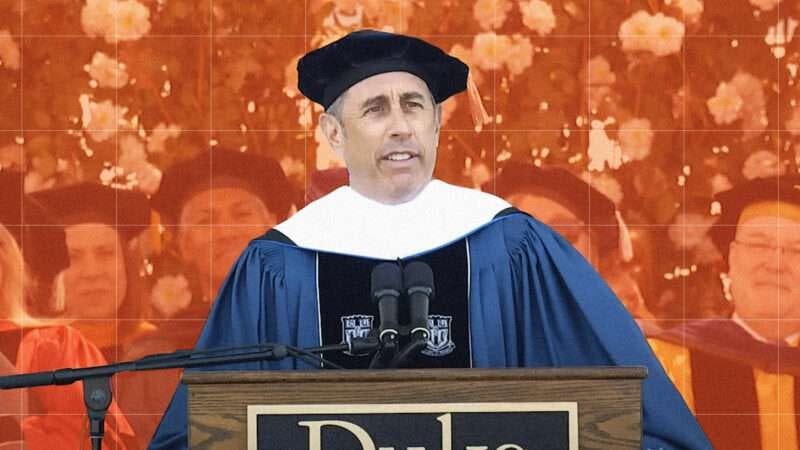

This was formative, and I thought of it this past weekend as I read about students walking out of their commencement ceremonies in protest. There are a number of examples, but perhaps the most high profile instance was at Duke University, where a group of students left the ceremony as Jerry Seinfeld received an honorary degree and before he spoke because, as one of the protesters told the New York Times, “none of us particularly wanted to listen to Seinfeld.”

I’m not going to get into the weeds about the issues here, except to say that I’m much more aligned with the protesters’ views on the war in Gaza than I am with Seinfeld’s. But, the image of students walking out of their own commencement ceremony brought me right back to that morning in chapel and I felt, as strongly as I did then, that there has to be a better way to express disagreement.

Walking out communicates that no further conversation is necessary or possible. It says, my mind is already made up and nothing you have to say can convince me otherwise. In the case of Seinfeld, who clearly was not going to address the war in his commencement speech, it says, your entire identity has been reduced to this one view, and that view puts you beyond the pale.

It’s a difficult balancing act; protest should be disruptive, it should make one’s views clear and should have the effect of rallying others to one’s side. But I also think it should be the beginning of conversation and dialogue, not the end. Otherwise, it is merely performative, centering the attention on the protesters themselves and not the issues.

Of course, protest can lead to dialogue; we’ve seen it. In instances where university administrators didn’t just rush to send in police to break up encampments, where protesters dispersed peacefully, it was because a dialogue was started. Brown University’s administration was among the first to take this approach. Over the weekend when Harvard became the last university in the Boston area to ends its encampment, it did so without calling in police because the administration committed to dialogue. This is as it should be.

Here’s another core memory. I’m in high school at Malden Catholic. Ms. G is my religion teacher. One day I see her leaving school in a car with a bumper sticker that reads “Trust in God. She will Provide.” As a fourteen-year-old born-again Christian, I was horrified—angry. But she was my teacher; I couldn’t walk out on her or refuse to listen. She’d be a part of my life, a part of my education, for the next four years.

Do you know what happened? Over those four years, I was changed. I listened. We dialogued. I was young and just learning how to be in the world. She was older, and wise. What Ms. G taught me about love and acceptance, about the importance of listening with an open mind, formed me, so that on that day in chapel at Gordon, I was ready to listen to the guest speaker and horrified by those students who made an embarrassing show of their displeasure.

I still had a lot of learning to do—still do. But, I knew then that it wouldn’t happen—couldn’t happen—without an open mind. That I would never evolve, and would never convince anyone else to change either, if I wasn’t willing to listen.

Nice. Chapel credits were like gold--shame to waste them on a "protest." I'm always surprised when people walk out of anything...like the movies. Too expensive to boycott.