Frankenstein AI

Mary Shelley's monster is an apt metaphor for AI, but maybe not how you'd think

Frankenstein is hot right now. While Mary Shelley’s novel, which turned 200 years old in 2018, has never faded from the cultural consciousness, it’s experiencing something of a renaissance. This year, two movies—Lisa Frankenstein directed by Diablo Cody and Poor Things starring Emma Stone—adapted the novel for contemporary audiences. Next year, two more films based on the story are set to premiere—Guillermo del Toro is filming an adaptation starring Jacob Elordi and Oscar Isaac, and Maggie Gyllenhaal has a take on the story titled The Bride with Christian Bale as Frankenstein’s monster.

And it's not just film; fans of Taylor Swift noticed a flurry of Frankenstein references in the music video for “Fortnight” from her latest album. A recent GEICO ad showcases Frankenstein’s monster—well, actually, he explains, he’s not Frankenstein’s monster, but they grew up together (and look a lot alike). Gen Z has Frankenstein fever too—several of my students this year cited the book as their favorite. And, on social media, TikTok’s BookTok in particular, Shelley’s novel stars in thousands of short videos (#frankenstein).

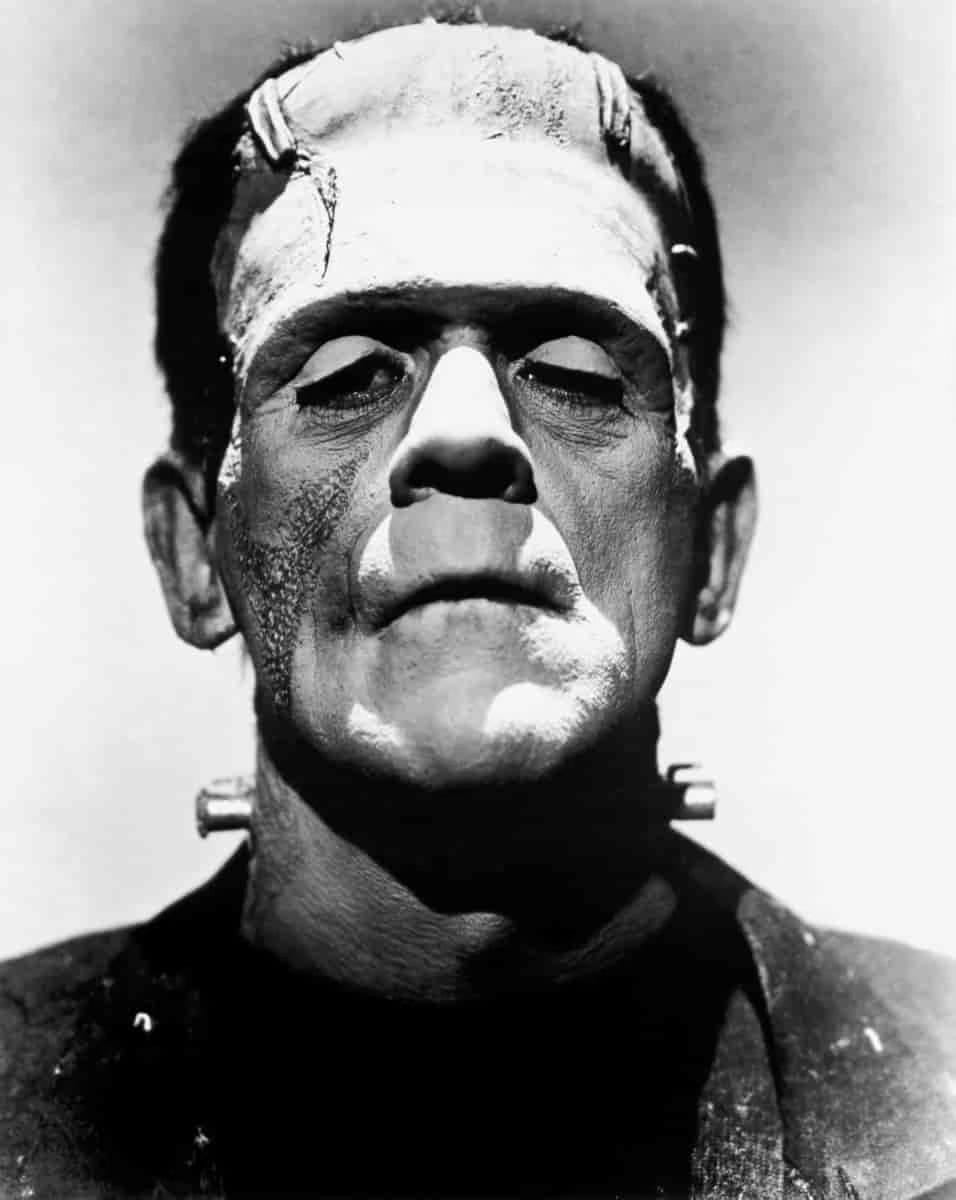

Perhaps it’s not surprising that a story about an inventor who loses control and is ultimately terrorized by his invention should resonate now, given the seemingly sudden proliferation of artificial intelligence. That’s part of it, I’m sure; but the connections to AI run deeper. While pop cultural depictions of Frankenstein’s creation, which date back to the 1931 film starring Boris Karloff, play up his inhuman qualities—the flat head, the green skin, the bolts protruding from his neck—what is often lost in these cartoony depictions is the fact that the hideousness of Mary Shelley’s monster derives not from his dissimilarities from humanity, but rather his likenesses—the ways the creation reflects its creator.

Frankenstein is finding new audiences today because the novel’s infamous creature—fabricated by Victor Frankenstein from human body parts retrieved from graves and dissecting rooms—is an apt metaphor for artificial intelligence. In our time, the technological titan is built not from human parts but human data—our correspondence and culture scraped from the internet—and what it shows us about ourselves can indeed be hideous.

Much like the perception of AI in these early days, Frankenstein’s intention and first impression of his invention is all possibility. He imagines a new species that would claim him as its creator and, ultimately, overcome death. Of the creature who he crafted with “infinite pains and care,” Frankenstein says, “his limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful.”

This beauty is short lived; when the creature comes to life and opens his eye for the first time, those same beautiful features become hideous: “his yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath” and though he had “lustrous” black hair and “teeth of a pearly whiteness,” Frankenstein adds, “these luxuriances [sic] only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes…shrivelled [sic] complexion, and straight black lips.” In the end, Victor Frankenstein says, “the beauty of the dream vanished and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.”

The creature is hideous precisely because the sum of its parts—its beautiful features—add up to something less than human. It presents a distorted reflection of the humanity of its creator. This metaphor figures prominently in the first filmed version of the story, a 1910 silent short produced by Thomas Edison’s studio. In the film’s final scene, as Frankenstein stands in front of a mirror, he is terrified to see his monster’s visage reflected back at him.

As the reality of an AI-future moves from the fantasy of science fiction into our homes, offices, and classrooms, the story of an inventor whose desire to allay death causes him to create a technology that he ultimately can’t control is one we are drawn to, in much the same way that, at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, there was a spike in viewership for films like Contagion that dramatized our real life catastrophe.

But there’s so much more to the story than Hollywood tales of reanimated corpses and The Munsters reveal. Frankenstein is a truly terrifying novel, yet the terror comes from the recognition of our own human failings—the good intentions gone wrong, the horrifying hubris that leads to the invention of a kind of gothic artificial intelligence in the distorted image of man. What truly terrifies us is the way that Frankenstein’s failed creation reflects and reduces humanity to its basest parts.

Given the prevalence of these themes in our culture at the moment, we can see semblances of Frankenstein everywhere, even when the reference is unintentional. When Apple announced the release of its latest iPad in May, the device was overshadowed by the ad that the company created to sell it.

In the ad, titled “Crush,” a massive hydraulic press literally crushes physical embodiments of human creativity including musical instruments, artists’ paints, typewriters, and turntables. When the press lifts, the new iPad—the thinnest and most powerful ever, the voiceover announces—is revealed. Apple is known for advertisements that make bold statements, but the depiction of the destruction of creative objects in “Crush” struck a chord for the wrong reasons, and viewers took exception. Will Shanklin, writing for Engadget, noted that the ad dropped just weeks before Apple is set to introduce a suite of generative AI features on its devices. “Context is everything, and Apple failed spectacularly there,” he writes. Apple has since apologized for the ad, claiming its message “missed the mark.”

Actually, I’d argue that its message hit the mark dead on—it just isn’t the message Apple intended. Viewed in light of Frankenstein, the ad depicts with arresting visuals what it looks like when we allow hubristic tech companies to compact the raw materials of human creativity into AI, thus endowing it with a fabricated semblance of a creative impulse of its own.

For over 200 years, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has been teaching us that when we try to invent using our own humanity as the raw material, the creation will always be a distortion, ultimately less than the sum of its parts. We’ll see something of ourselves in it, but the image will be deformed—a hideous monster staring back at us from the mirror, or, as it may be, from the screen.