Musicianship, Nihilism, Authenticity . . . and, um, Marilyn Manson? - Issue #21

Jason comments on the Marilyn Manson sex abuse scandal, but mostly explores his own longstanding and fraught interest in "extreme" music

1.

Marilyn Manson is finished.

There is no comeback tour down the road. You heard it here: he’ll quietly, ignominiously slink back from public life, and be essentially a non-entity until 5 or 10 or 20 years from now when his obituary hits the social media feed of the New York Times, and we collectively say “Oh yeah, that guy.”

In one of the more decisive instances of a prominent cultural figure facing allegations of abuse and assault from past victims, the notorious singer has been dropped by his longtime manager, record label, and talent agency, and digitally erased from unaired episodes of the Starz series American Gods. The revelations from a variety of ex-girlfriends and associates about his peacocking control-freak cruelty and sexual sadism—the latter of which, by almost all reports, went well beyond established BDSM practices concerning safety and consent, though Manson somewhat feebly insists otherwise—have been rock-solidly consistent, well-documented, irrefutably credible, and absolutely damning.

Manson, there can be no doubt, was a genius at leveraging shocking and iconoclastic performative imagery into a highly-successful band and brand. He also endured (or, more likely, reveled in) accusations of poisoning the values of late-90s teenagers, and even of complicity with the Columbine murderers. He obligingly played the new boogeyman in the twilight of the moral panic about popular music that began with Elvis’ gyrating groin, gained steam with Led Zeppelin’s alleged Satanic backmasking, and reached its apex with Ozzy Osbourne, Tipper Gore, and anything Dr. Dre was involved with. And he has now answered a pair of questions about artistic extremity, questions that he has coyly embodied for over two and a half decades: To what extent is it genuine? To what extent is it show-biz?

These are questions that always bubbled up when I got interested, as I often did, in music that embraced a sort of artistic extremity. There are plenty of bands whose work is abrasive and nihilistic to the point that one might reasonably assume the artists themselves are profoundly incorrigible obsessives whose work entirely and unironically reflects their real lives. Theirs are works that, as you listen to them and peruse the album art, it seems as though the music and imagery sprung fully formed from the band’s collective id.

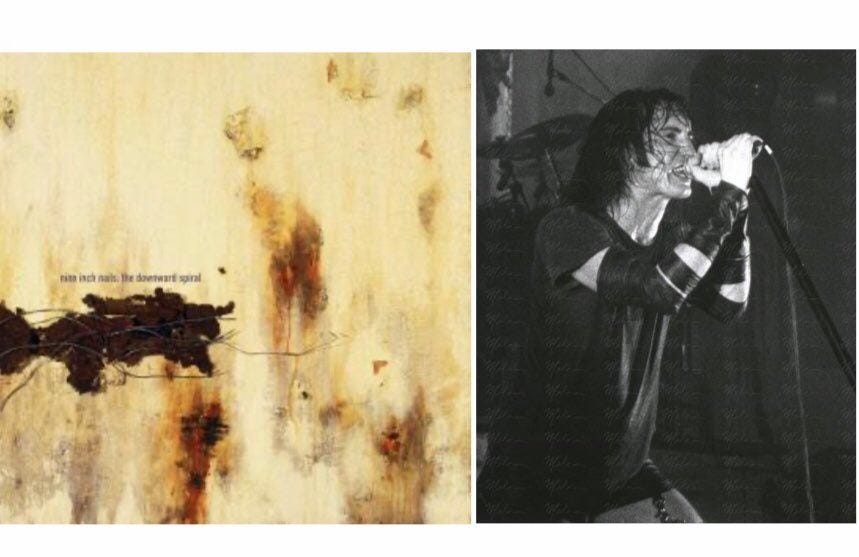

I remember putting Nine Inch Nails’ mid-90s masterpiece The Downward Spiral into my CD player when I was 14 and flipping through the CD booklet as “Mr. Self Destruct” blared into my bedroom. I’d never heard anything like it. I still find the album cover unaccountably haunting, especially that shit-colored and vaguely-human-shaped rust stain. Rationally, I knew that this record was the product of hard work and planning and writing and musician-hiring and rehearsing and performing, followed by a variety of business and PR wrangling.

But I couldn’t hear the music or see the album art as the outcome of such things. It seemed impossible that anyone sat down and planned this thing, or that it had to be reviewed and promoted by actual businesspeople and marketing firms.

Instead, it was as though Trent Reznor’s psyche had spontaneously exploded, and someone just plucked this cardboard-and-plastic commodity from the rubble.

2.

In 1992, three years before I got my hands on The Downward Spiral, I received my first CD player, a Sony boombox with detachable speakers, from my parents for Christmas. It was the first CD player that had ever been in the house (I’d grown up with my parents’ turntable and enviably-stocked collection of oldies vinyl, as well as one of those dual tape decks that let you make copies upon analog copies) so they thoughtfully included a CD, a Time-Life collection of classic rock songs, all focused around great guitar players.

I was learning guitar myself at the time, so I liked this collection quite a bit. It was my introduction to Jimi Hendrix and Jeff Beck, and even the first time I can remember hearing Clapton, at least outside of that Grammy-sweeping Unplugged release.

But there was another album I wanted even more, one I knew better than to ask for as a Christmas gift.

A few days later, armed with cash from my paper route tips and gift certificates from the holiday, I joined my family on a trip to Bradlee’s, a down-scale regional Kmart sort of place with a surprisingly decent music selection. As I often had before, I peeled away from my parents, claiming I wanted to browse the racks while they went off to look at, I don’t know, shower curtains, maybe? But instead of browsing, I went straight to the “G” section, plucked out Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction, snuck to the checkout, paid for it, tucked it under my jacket, and doubled back into the store to find my parents. When we got home, I hid it behind my bookcase and proceeded to listen to it only through headphones for the next two years.

GnR was, in many ways, one of the safest groups for a small-town 11-year-old to be exposed to. Their lyrics and image were crude, but their overall ethos was about as normative as they come. Sex, drugs, and rock and roll had been old news for over two decades. Nonetheless, I was positive that this was a dangerous record. The band name, the album title, the iconic-but-cheesy Celtic cross festooned with each band member’s skull that made up the cover art; the Taxi Driver-ish urban nightmare laid out in “Welcome to the Jungle”; the matter-of-fact descriptions of heroin addiction in “Mr. Brownstone”—I took these things very very seriously.

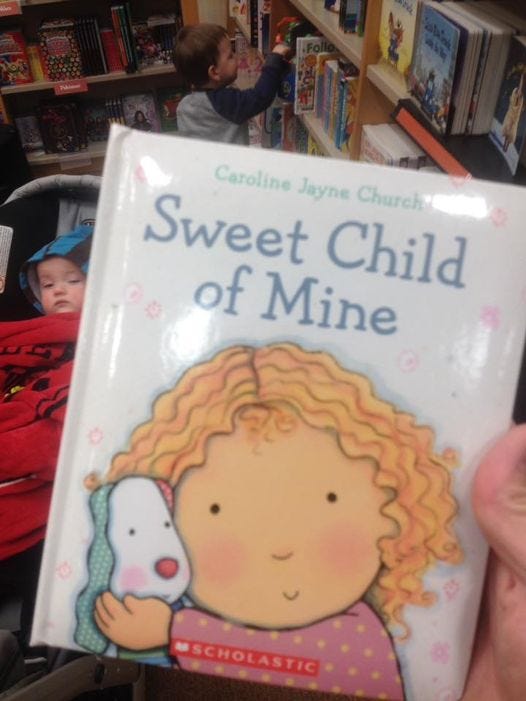

Of course, “Sweet Child O’ Mine” should have been the tip-off. The opening guitar riff is so ubiquitous and beloved that it appeared, along with “Stairway to Heaven,” on a sign in the guitar shop I frequented throughout high school. The sign’s function was to list riffs that you were forbidden to play while test-driving an electric guitar, presumably because the staff was sick of hearing them. And no wonder. It’s as inevitable and instantly recognizable as “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” or “Happy Birthday.”

And have you ever actually read the lyrics to “Sweet Child”? They’re quite wholesome. It might as well be a Johnny Mathis track.

But my point is that even with the saccharine awesomeness of “Sweet Child” staring me in the face, I felt certain that the band members themselves were still the reckless, hard-living, real-deal scourge of the Sunset Strip, giving the finger to authority and saying “Society sucks, man!”, even as they went on to become millionaires—I didn’t pick up Appetite until 1992, after all, well after the hypercommercialized Use Your Illusion albums had dropped—making shiny and expensive narrative music videos about the trappings of being married to supermodels, brimming with the pure essence of Axl’s ego. As drummer Matt Sorum put it: “I was in the most dangerous rock and roll band in the world at that time . . . Along came pianos and these epic 10-minute opuses. I was surprised.”

But of course, it’s no surprise that musicians, including some of the most beloved and iconic, attempt to maintain a particular persona that at once enriches and complicates and (once in a while) contradicts the nature of their music. The list of bands and performers that I came to love as a teenager and adult is filled with examples of this across all kinds of genres, from Johnny Cash to NWA. Was Cash singing murder ballads because they’re good country songs? Because they expressed some repressed but persistent desire? Because the troubled alcoholic and amphetamine abuser had intimate experience with the subject matter? Or maybe, because his persona, The Man in Black, the guy who could hold his own on a stage in front of hardened convicts, was the one who had such intimate experience? Where did the man end and the persona begin?

As for NWA, Ice Cube addressed this question of authenticity head-on:

“We deal with reality, plus we say what kids want to hear . . . Some of my friends are gangbangers, so I pretty much know how they feel, I know why they do the things they do, I just put it on wax. The people who are scared are people who don't know.”

3.

In the second half of my high school years, as I became more serious about the guitar and took classes in music theory, my tastes shifted toward artists who seemed to me to be not only more technically proficient, but whose musicianship was their identity. After dabbling in the subtly-jazz-inflected work of Stone Temple Pilots (even my extremely snobby guitar teacher conceded that they were more musically sophisticated than your average grungy post-Nirvana band) and jam band noodling of Phish, I went on to get REALLY into albums by Steely Dan, Yes, Pat Metheny, Juliana Hatfield, Brian Eno, Primus, Metallica, King Crimson, and Frank Zappa. Senior year, I went down a vintage jazz rabbit hole, binging on Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Cannonball Adderley. I spent almost a year, pre-Google, trying to get ahold of a seemingly-elusive Charlie Parker recording of “Mounds of Time,” only to finally learn that I’d misheard the title and what I really wanted was called “Now’s the Time.”

What drew me to this assortment of major-league-talented and idiosyncratic performers was the idea that, far from having some sort of manufactured identity that they played as dead serious, they seemed to embody an erudite and all-consuming drive to perfect the music itself. As I tried to learn and execute Phrygian scales and weird chord voicings, and began assembling audition tapes to accompany my college applications, this mentality gained more and more appeal. Just as Alexander Pope argues in An Essay on Criticism that poetry is a skill and craft to be honed and developed (“True ease in writing comes from art, not chance / As those move easiest who have learn'd to dance”) as opposed to the more romantic notion that poetic greatness is within the reach of any old person who is sufficiently in touch with their own emotions, I liked the idea that real music was the preserve of people who could, for instance, tell a D7#5#9 chord from the vastly different D7#5#9sus4.

I was pretty insufferable.

What I realize now is that all of the artists I mentioned here, to one degree or another, did not promote themselves as inscrutably dark and foreboding figures. Phish, for instance, as goofy as they are and as much as cultural commentators enjoy dunking on them, are absolute masters of their instruments. When they want to, they wail harder and tighter than any band out there, ever. They have a host of extra-musical quirks: trampolines, long-running chess games against fans, a cult following that makes 80s-era Deadheads look down to earth. But it’s clear that musicianship, performance, and collaboration are the priority. Primus, similarly, is basically the musical embodiment of off-the-wall eccentricity, but it never feels as though you’re obliged to take anything about them seriously, aside from Les Claypool’s brain-melting bass chops. Metallica had some sociopolitically-critical lyrics on Ride the Lightning, Master of Puppets, and the sonically bizarre And Justice for All, and occasionally reveled in gruesome imagery (especially on Black Album tour merch), but they also made it clear that, at least during their 80s golden era, they were fun-loving hard partiers and pranksters, dorky metal kids who were disciplined and talented enough to make an astonishingly successful career out of it.

If these bands had an identity beyond their music, it was whimsical, malleable, or incidental—not humorless and all-consuming and vaguely ideological. Even Frank Zappa, who was an unapologetic weirdo, always seemed to place his own virtuosity well ahead of any look-at-me gimmickry.

And yet, as I’ve grown older and gone through (sometimes obsessive) phases of listening to various versions of just about any music genre you can name, I’ve consistently come back to bands whose music feels genuinely infused with grim dissolution, and who seem to live and breathe that element of their work. Wu-Tang Clan’s The 36 Chambers, another album I listened to clandestinely for a few years in middle and high school (though this time it was a cassette copy of a friend’s CD), seemed authentic. Converge’s Jane Doe, with its ferocious time signature changes and visionary/anal-retentive production, seemed authentic. Deafheaven’s primal shrieking and tidal waves of overdriven guitars on Sunbather (0:24 on this track hits like the hammer of the gods) seemed authentic.

Like The Downward Spiral, these records appeared, more than anything, to exude a not-messing-around quality that led me to believe, even when I knew better, that the aesthetics of the music were inseparable from the lives of the band members.

Converge, for instance, is an acclaimed and technically superb hardcore metal band whose albums are relentlessly packed with bleak imagery. The release of their fearsome 2017 album The Dusk in Us occasioned a rave review from the Boston Globe that also gamely explored the question: “Why do we crave challenge from film and fine art while we implore music to comfort?”

However, Converge guitarist Kurt Ballou is known to affably nerd out as a guest speaker at Berklee-sponsored music engineering symposia hosted by, of all people, Prince’s sound engineer. One time, I thought I saw him at the Children’s Museum in Boston, toddler in tow; it turned out not to be him (I asked), but it felt entirely plausible that he’d be a guy who would have that kind of wholesome family-oriented Sunday afternoon. But with other, similarly intense musicians who cultivate a certain sort of withdrawn or ascetic or tortured image of the artiste, it’s almost impossible to imagine that they do much of anything other than brood and experience sublime bursts of romanticist creativity.

My preoccupation with those kinds of artists is best summarized by the fact that, although I have little interest in actually listening to Norwegian black metal pioneers Mayhem—De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas is probably the most uncompromisingly evil-sounding and offputting record I’ve ever listened to all the way through—I greatly enjoy reading about their offstage lives. I would be embarrassed to admit how many times I’ve watched scenes from Lords of Chaos on Hulu. And I don’t even mind that it barely focuses on the band’s music, and almost fully devotes itself to exploring whether their Satanic and antisocial imagery was borne of true-believer conviction or poseur gimmickry. The film seems to come down firmly in favor of the latter. At one point, a band member is interviewed by a journalist who, immediately after, remarks “What a fucking idiot,” and it’s clear that we are meant to agree.

But this actually makes for a far more compelling story. To anxiously strive to embrace a genuinely uncompromising ethos, and to repeatedly fail—for someone like me, who grew up persistently confusing personal identity with musical taste, that’s the stuff that’s interesting, far more so than pentagrams and guttural vocals and blast beats.

4.

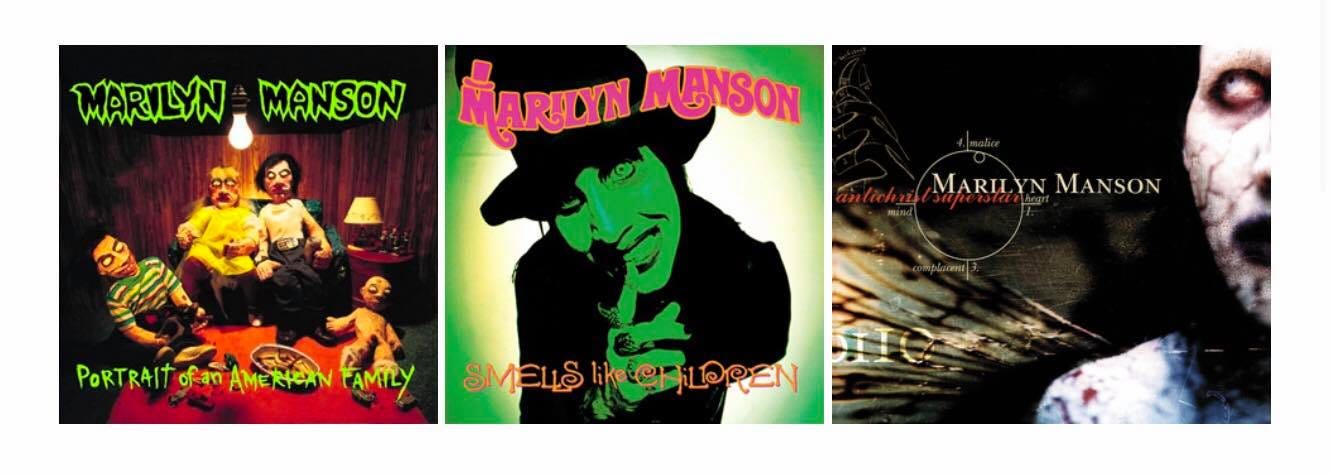

OK, no more dancing around the point. I was a fan of Marilyn Manson, at least for his first three albums: the grimy white trash pastiche of Portrait of an American Family, the experimental hallucinogenic freakout of Smells Like Children (an album my grandmother bought for me during a visit to Florida, which I’ll always feel kind of bad about), and the hit-or-miss attempt at high-concept Miltonian art metal of Antichrist Superstar.

And let’s be honest, a lot of Manson’s stuff from this era, if you’re able to separate it from his vaudevillian grotesquery, just kinda rocks. Much of the music, in and of itself, isn’t any more subversive or daring than any number of records that have come out since, say, Black Sabbath’s Paranoid. “Lunch Box” is catchy as hell, like a slightly more debauched version of an early Stooges song. “Tourniquet” and “Beautiful People” blend industrial rawness with thrash metal stylings in a way that’s satisfactory, but not exactly visionary. The covers of songs by Patti Smith, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and, most notably, The Eurythmics, are solid as hell, and are mixed in with sound experiments and spoken word pieces on the Smells Like Children EP that probably would have felt more unsettling if I hadn’t already been exposed to the Beatles’ “Revolution 9”, which, back when I was 11, had made me profoundly uncomfortable.

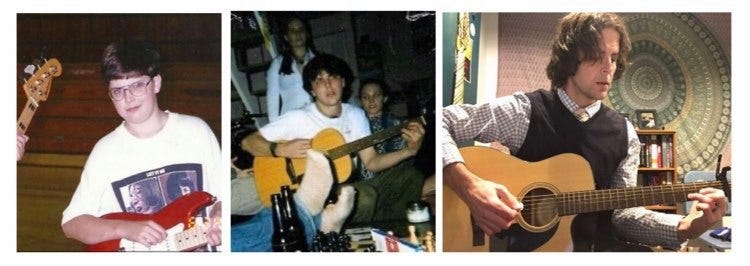

I was so enamored with Manson’s ability to rev up classic rock and new wave standards, and to make them both ugly and immaculately produced and performed, that I proposed to the metal band I was playing in in 10th grade that we do a cover of Manson’s version of “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” for the school talent show. The riff and solo were easy to play, and the power chords had a bracing simplicity. We rehearsed a few times, put microphones around the drum set and amplifiers so the whole thing would come out brutally loud through our high school auditorium’s PA, and played it for a crowd of maybe 800 people. Not to brag, but we kinda nailed it, and I’ve got my parents’ home movie collection to prove it. That’s me way over on the the right singing and playing the sunburst knockoff Les Paul, doing my best to be intense and unsmiling:

But even then, I was determined to maintain a sort of clinical or scholarly distance from Manson’s ideology and persona. I didn’t want to actually be a Marilyn Manson fan, even as I liked a fair amount of the music, because I had hard opinions about the trappings of that particular subculture. Being an actual Manson fan, as my judgmental 15-year-old brain understood it, meant a gothy wardrobe, clinical depression, and terminal misanthropy. It meant being from a broken home. The brokedown ennui of economically-depressed suburbia or small town America. Self-harm and a too-early cigarette habit. And, of course, eventually, it even came to signify the pathologized rage of the school shooter.

None of this was fair of me, of course. My conception of the stereotypical Manson fan was a contrived and reductive archetype. But I couldn’t shake the idea that if my appreciation of Manson’s music went beyond noting that several of their songs were pretty fuckin’ great, if it dipped into the dark cultural signifiers, I’d be taking on an identity that I wasn’t interested in. I wasn’t depressed and didn’t hate my parents and didn’t want to wear black clothes and nail polish and chains, and so, I thought, I couldn’t really be a fan.

This perspective was thoroughly challenged at the beginning of my sophomore year of college. I transferred to UMass Amherst to study English after one highly-disappointing year of studying music at Lowell during which I was confronted with the fact that I was okay at guitar, but . . . yeah. Only okay. Since I was new to Amherst, I was randomly paired with a first-year student as a roommate. He was—how best to put this?—what we would now likely call a “bro.” Muscular, crew-cut, chinstrap beard, strong Boston accent. Lots of Adidas clothes. He kept a chintzy-looking neon-green plastic bong on his dresser. He was a hard partier who would hit the gym, then down a 40 and a calzone. He was a friendly, outgoing guy.

After we first met, I left our room to buy books and explore the campus. When I returned, he’d settled in and put up some décor, including not one, not two, but three garish, blacklight Marilyn Manson posters. I hated having to look at those things all year. They were ugly. They did not accord with the “chill” tapestry-and-incense vibe I wanted to cultivate. My preference at that time was more Portishead and A Tribe Called Quest and the Grateful Dead than Mechanical Animals, and I made sure every visitor to my room knew within the first three seconds: Those posters aren’t mine.

How, I wondered, did this dude who could plausibly have been Homecoming King in high school, and will undoubtedly be rushing a frat in the near future, get so into Marilyn Manson?

There was no black nail polish in sight.

A Conclusion

The central revelation of the allegations against Manson is not, of course, that, disturbingly often, powerful and narcissistic male media figures use their access to industry resources and networks to extort sexual favors. That fact has been amply demonstrated over the past several years. Nor is it necessarily surprising that such extortion led to long-term abusive relationships, Stockholm Syndrome-esque trauma, and, in some cases, physical scars. The #MeToo movement has done a lot of good in the last four years, and one of the tougher-to-swallow pills it has offered us is that this kind of behavior, far from being rare or scandalous, is practically banal in its frequency—shocking, but not surprising.

What has been revealed, however, is exactly the opposite of what I always suspected about Manson. One of his victims, in the New York piece linked at the beginning of this essay, points out that all of Manson’s fetishistically violent practices were hiding in plain sight, woven right into his lyrics and videos, into his whole persona. Why, one might think, should we be at all surprised that a man who embraced abject representations of sexuality and power in his art also embraces abject sexuality and power in real life?

Well, honestly, I always thought that his schtick was so over-the-top, so campy, so seeped in bad-horror-movie histrionics, so clearly calculated to scare the shit out of the middle class and middle America, that it couldn’t really be a glimpse into his real person. I guess I figured that he wrapped up each day of being Marilyn Manson by taking off the makeup and off-label prosthetics, putting on sweatpants, ordering a pizza, and watching Friends reruns.

I suppose I suspected that a person as ostentatiously subversive as Manson purported to be must really, after working hours, be as vanilla, or at least as civilized and decent, as they come.

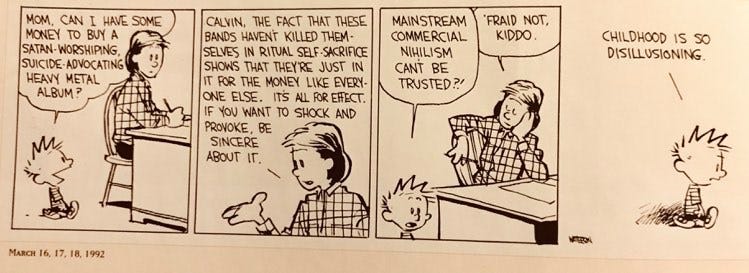

This suspicion was clearly, dramatically wrong. Perhaps, sometimes, contrary to Calvin and Hobbes, mainstream commercial nihilism can be trusted.

The views expressed above are solely those of the author.

If you enjoyed this article, please share and subscribe!

Nice piece, Jason. I can relate.

I don't know who I find more loathsome at this moment, Marilyn Manson or Ted Cruz. Both are rightfully ignominious simultaneously in culture, although that assumes either of them had a shred of dignity before their current disgrace. Frankly, it's hard to look at either of them, let alone take them seriously. They are monsters who should scare all of us.

Then again, maybe I'm not the best judge. When I was eleven-years-old, I pretty much avoided the Rock section of our local LP emporium, Musicland at the Imperial Mall in Hastings, Nebraska. Convinced that Led Zeppelin, the Grateful Dead, and Jefferson Airplane were virtuosos of Satan, it seemed highly transgressive even stepping into the store on my way to the Barry Manilow section.

Hastings had an actual K Mart, and buying my eight tracks there seemed more wholesome and American.

I've put away childish things since then, and have come to truly adore the musical majesty of Zep and the sublime Americana of the Dead. The thing is, I grew up. Plant and Garcia were already great, I just had to listen and learn. Of course, Jefferson Airplane became Jefferson Starship, which is a tragedy too gruesome to describe in this posting.

Neither Cruz nor Manson have evolved into anything more than petulant, soft-core wannabes. Performing for smaller and smaller audiences each must increasingly rely on "schtick...so over-the-top, so campy, so seeped in bad-horror-movie histrionics, so clearly calculated to scare the shit out of the middle class and middle America..." (That's a truly amazing sentence, Jason!)

I hope Marilyn Manson is finished. Found guilty of the accusations would only underscore his monstrosity. Cruz will probably survive his disgrace, but he can't take off his makeup.