There's Nothing Christian About Evangelicalism

The bargain evangelicals made with Trump in 2016—fealty for pro-life judges—has permanently altered the entire movement

I was 16 years old when news of the Clinton-Lewinsky Scandal broke in January 1998. Like most teenagers, I wasn’t particularly political, but, unlike most teenagers, I was very religious, and thus without knowing much, I knew what side I stood on. Clinton, as a Democrat, was bad—though the main thing I knew about Democrats is that they were pro-choice. And, of course, having an extramarital affair with an intern was also bad. Two strikes, Bill.

That said, besides maybe some inherited cynicism about politics and a teen’s secret fascination with the bawdier details, I don’t remember the scandal impacting my life very much. Until it did.

At the time, my family was attending Grace Chapel in Lexington, MA. Not long before, we had made a formal split with the church that I grew up in, the church my parents helped found. My mom and I talked often in those days about the reasons for the move, and a lot of it came down to significant differences with the leadership style of our old church’s head pastor. At Grace Chapel, we found a leader we could look up to.

Gordon MacDonald was smart, educated. He was an author, and he had led major Christian organizations including World Vision and InterVarsity. But also, by this point, he was a man marred by a sex scandal of his own. In 1987, it came out that he had had an affair. Overnight, everything that he had built—including his reputation—was ruined. He disappeared from the public eye, and subjected himself to the mentorship of elders and friends, including R. Judson Carlberg, former president of Gordon College. Then, in 1993, satisfied that he had repented and reformed, Grace Chapel invited him back. It was a controversial decision, but ultimately the congregation accepted him.

By 1998, MacDonald was redeemed. He had written several books about his downfall and what he learned including Rebuilding Your Broken World, published in 1988, and The Life God Blesses in 1994. Bill Clinton had reportedly read MacDonald’s Rebuilding twice after his scandal broke, so it was perhaps not surprising that he called upon MacDonald to counsel him.

I remember news crews with their vans and cameras surrounding the church on the Sunday when MacDonald informed the congregation at Grace Chapel that he had been advising Clinton, and I remember feeling conflicted. I would have preferred to continue engaging in schadenfreude over the Clinton scandal—we knew he was bad! And yet, here was MacDonald, our pastor, who we had grown to love and trust, telling us that he was attending to Clinton’s genuine desire for redemption. I remember MacDonald preaching a sermon on David and Bathsheba.

In retrospect, this episode was formative to my sense of what it meant to be a Christian. And even as I moved away from the evangelicalism of my youth, I felt I knew and understood the movement. I don’t anymore.

Earlier this week, my friend Seth—himself a pastor—directed my attention to a New York Times article titled “Piety and Profanity: The Raunchy Christians Are Here.” It was written by Ruth Graham—a graduate of Wheaton College (Illinois) and exactly the right person to be writing about evangelicalism for the Times.

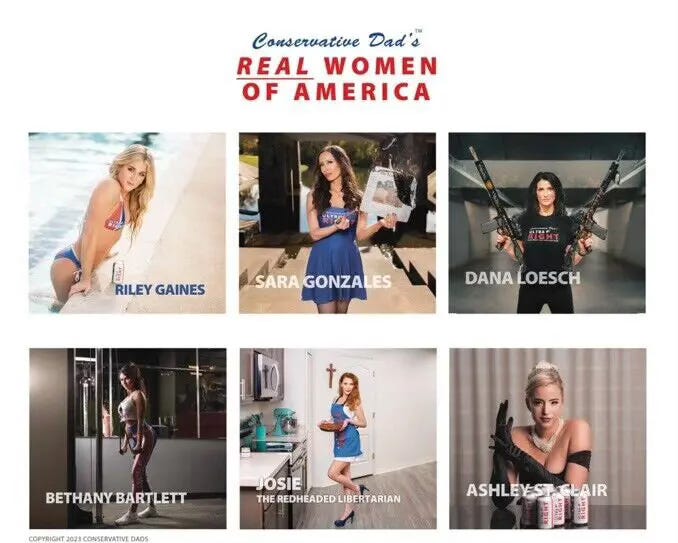

Graham begins the article by describing the “Conservative Dad’s Real Women of America” pinup calendar, which features salacious pictures of pro-Trump women—“influencers and aspiring politicians.” The calendar illustrates a new trend in Trump-era evangelicalism—I’ll return to that word in a bit—that offers not just a reluctant acceptance of the former president’s lewd style, but indeed an embrace.

Graham cites several examples beyond the pinup calendar to illustrate the ways in which profanity has overshadowed piety for many so-called evangelicals. The reasons are many—Jake Meador, who edits Mere Orthodoxy (longtime readers would remember Mere Orthodoxy as a kind of mirror-publication to Patrol, the site I edited with David Sessions), notes that shift toward profanity follows the norms of online discourse: “the way you stand out is by being the most devoted, the most extreme in the cause.”

Kristin Kobes Du Mez, Calvin University professor and author of Jesus and John Wayne, links the embrace of vulgarity to “deep conservative outrage, an often visceral disgust, at rising rates of nontraditional gender and sexual identities.” In the face of this, showing some strong heterosexual desire—even lustfulness—has become, amazingly, a way of fighting back.

It goes without saying that this new iteration of evangelicalism—a term that we used to argue over, but which has now been fully ceded to the MAGA-Right—has lost any semblance of touch with traditional, orthodox Christianity. The bargain it made with Trump in 2016—fealty for pro-life judges—has permanently altered the entire movement. This version of evangelicalism could never even feign moral outrage at a sitting president’s marital infidelity. But perhaps even more devastating, this version of evangelicalism could never be called back to the fundamental values of forgiveness and redemption as Gordon MacDonald encouraged the congregation of Grace Chapel, and me, to in the mid-90s. The only way to get these Christians to open the Bible, it seems, is to rebrand it as patriotic propaganda that mainly serves to line Trump’s pockets…what was it that Jesus said about a “den of robbers?”

Seth, who brought the Times article to my attention, maintains that among Christians who regularly attend church, the core of orthodox Christianity holds. That may be true, but the share of evangelicals who regularly attend church is declining precipitously according to Ryan Burge, who has become the numbers talisman of American religion.

In my recollection of the Clinton scandal and Gordon MacDonald’s involvement in it, I see two aspects of evangelicalism that no longer hold: a commitment to moral rightness and a call to live out Jesus’ teachings. It was right for Christians to condemn Clinton’s infidelity, but it was also right to believe in the power of forgiveness. This is what evangelicals used to call Compassionate Conservatism. I’d argue that evangelicals of today are neither—compassionate nor truly conservative.

You are absolutely correct, Jon. All throughout history, people have given up their allegiance to the teachings of Jesus and turned faith to the institutions which claim to embody those teachings. History teaches us that the institutions often fall far short of the teachings they proclaim as they fight, not to be in harmony with Jesus, but to bring greater and greater power to the institutions.

I don’t think agreeing with you is a good way to promote conversation. However, I cannot find a flaw in your article (maybe one grammatical error). Thank you for posting this article. While I became disillusioned with the Evangelical movement on political and theological grounds before Trump, I was proud of my upbringing as I respected the Evangelicals I knew and loved for their passion, character and consistency. While many continue to live admirable lives, the near wholesale abandonment of the movement’s ideals, and even their doctrine, in exchange for a demagogue with almost no affiliation or familiarity with their faith, and whose life and hateful speech was quite literally the antithesis of what they preached, now saddens me. More than that, it alarms me. It is essential for our society and culture to have bastions of morality to keep us in check. Now, the most prominent moral voice in our culture has been turned. That voice now spews hate.