Who Can Say "________"? - Issue #18

The Donald McNeil debacle is being disingenuously characterized.

In only the most recent scandal to upend the New York Times’ typically staid and stern PR image, the venerated science and health journalist Donald McNeil Jr. was relieved of reporting duties after a substantial contingent of his colleagues demanded consequences for his comments to a group of high school students—comments that included the utterance of the most incendiary and heinous of racial slurs.

Even if you know nothing about this story, I am sure you know exactly which racial slur I’m referring to.

That’s kind of my point.

Of the various reactions circulating about McNeil’s ouster, one of the most persistent and pernicious is that, since he was not using the word as an epithet or expletive, but rather engaging in a discussion about its historical and contemporary usage as an epithet and expletive, his firing suggests that people are not “allowed” (such arguments are often disingenuously made in terms of what is allowed or disallowed, rather than what is thoughtful or necessary or bound to trigger undesirable consequences) even to discuss the permutations and contexts of hate speech.

What this ignores is that McNeil allegedly made a variety of comments on this trip that ranged from questionable to aggressive. One student told the Washington Post that “Right out of the bat [sic] he was denigrating the medical traditions of Peru,” and that he allegedly “described nepotism as ‘affirmative action for White people’.” The use of the slur was not the entirety of his offenses, but a last straw.

Nonetheless, the focus on this incident has largely revolved around that one word. And that focus has dominated the backlash along with, as the Post puts it, “the backlash to the backlash.” The story has been misleadingly framed as an accomplished journalist losing his job only for having said it.

For instance, a statement from PEN America argues that “mention of the word—for example, in an attempt to clarify how it was used in another context—must not be treated as the equivalent of a racist attack.”

Indeed. But it is also worth noting the vagueness of the word mention here. Webster’s defines it as “act or an instance of citing or calling attention to someone or something” (my emphasis). Something can surely be mentioned, or even discussed at length, without the deeply problematic act of actually saying it.

Charles C.W. Cooke, a conservative libertarian editor for The National Review, whose work and personality I usually find likable despite all of those things I just mentioned about him, made a similarly disingenuous argument on his podcast The Editors: that the “vortex of illiberalism” has made it so that “discuss[ing] the use of the word in rap music or in historical American racism” is regarded as equivalent to using the word to hurt or diminish others.

To his credit, Cooke adds that, even in such supposedly intellectually-motivated conversation, he never uses the word itself under any circumstances. But his argument is still grievously ill-considered, because the Times fired McNeil for the word itself—and, again, even that was simply the final nail in the coffin—not for his thoughts about the word.

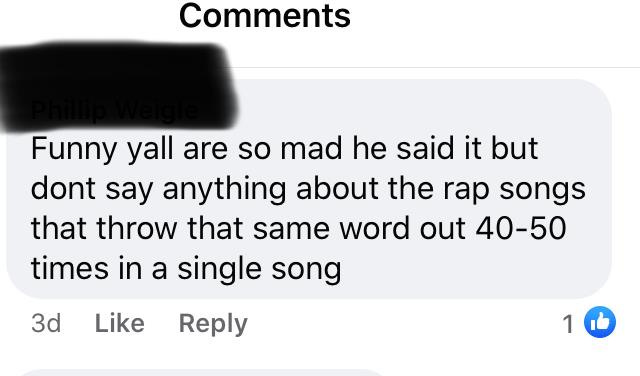

And furthermore, Cooke’s argument echoes an especially bad-faith talking point consistently offered up by white apologists for racist language, most recently in response to the minor scandal involving country music performer Morgan Wallen: What about rap lyrics? It’s a ubiquitous rhetorical question mired in blatant fallacy, musical philistinism, and apparent ignorance of the concept of reappropriation.

Considering that such commentary obviously offers “rappers” as code for “Black people,” it’s fair to say that this line of attack is undergirded by the belief that it’s not fair that Black people are often able to say this word with impunity, while white people are not. I believe, to put it in the plainest terms, that that is entirely fair, a position that has a rich discursive history.

And it is in fact stupefyingly easy to discuss the word in question without intoning or typing it, and even without leaning on its ubiquitous euphemism, the well-known affixation of the 14th letter of the alphabet to the word word. Its actual utterance, especially by a hyper-privileged white man (which, full disclosure, describes me as well as McNeil, Wallen, and Cooke), is not only profoundly unnecessary, but shows an excruciating lack of good judgment.

I don’t envy the New York Times. McNeil was a superstar reporter who broke some of the most important public health stories of the past year. The Times’ closest competitor in terms of daily newspaper prestige published a scathing editorial concerning the abrupt about-face performed by the management team, who had initially settled on a warning for McNeil and then capitulated to in-house pressure to let him go. They were put in a no-win situation that required them, once the story became public, to immediately and persuasively adopt a position on whether the use of a fraught word, in an analytic (rather than hateful) context, ought to be permissible.

Throughout my career as an English professor, I have at times taught texts that include the word in question: short stories by Flannery O’Connor and Philip Roth. Essays by Gloria Naylor and Randall Kennedy (whose most famous discussion of the topic was the inspiration for the title of this article). Films by Spike Lee.

In my second year teaching writing, at the University of Vermont, I made the (admittedly ill-advised) decision to have students analyze the lyrics of the title track to N.W.A.’s landmark album Straight Outta Compton.

It’s true that O’Connor, for instance, was a white Catholic woman from Georgia, and that her periodic use of the word is jarring and even potentially suspect. But one cannot deny that all of the texts I just mentioned meet the Huck Finn standard of holding legitimate scholarly, historical, intellectual interest.

On the other hand, I have permanently removed Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction from my film studies syllabus. Not because the word appears in it, or even because it’s periodically spoken by white actors/characters, but because it’s painfully apparent that Tarantino, particularly in his own poorly-acted cameo as a small-time criminal associate, is not speaking the word, or making his actors speak it, in order to convey a gritty sense of realism or make some sort of valuable point. He’s doing it because he relishes it.

Many commentators would surely claim that I’ve engaged in my own little performative moment of “cancel culture” or “virtue signaling” by removing a great film from the course. But I don’t care how brilliant the “foot massage” dialogue or the final scene in the diner might be. I can’t in good conscience assign and teach a film that uses racist language with glee rather than in the service of social critique and contemplation.

I have no doubt that Donald McNeil meant no harm or offense. And it’s a pity that his dynamic and consequential reporting will no longer be printed at the paper of record. My argument here is not about whether he should or should not have been fired, but rather about whether his firing signals a worrisome shutting down of good-faith dialogue concerning racist language. I believe that it does not.

But deciding to use the word itself is a conscious and highly conspicuous choice, arguably an act of verbal violence, and one that casts suspicion on any non-person of color who chooses to do it.

And, as I hope I have demonstrated in this essay, saying it is just never necessary. When a white person chooses to utter that word, it will, in my view, always come across as a provocation and an embarrassing attempt at iconoclastic edginess.

But this doesn’t mean that refraining from saying it is an outcome of censorship or of kowtowing to the allegedly unreasonable demands of woke culture. It’s neither. Rather, it is a gesture of bare-minimum decency, a silent acknowledgment from people who have not been historically oppressed by it that it is not our place to decide when or how a given usage ought to be considered acceptable.

The arguments and ideas expressed above are solely those of the author.

What I’m Reading: Lots of editorials about the McNeil incident, in preparation for this essay. Also, lots of editorials about the Democrats’ slam dunk presentation of evidence in the impeachment trial. And a little bit of Tom Perrotta, which is like my literary equivalent of comfort food.

What I’m Listening To: I’ve always been partial to early and mid-60s vocal-oriented groups. This genre was a big part of my parents’ record collection: Mamas and the Papas, Beach Boys, Peter Paul & Mary, etc. Lately I’ve been building playlists off of artists like this, and was especially enamored with this performance of “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).” I am always kind of especially interested in song lyrics that capture a certain time-specific zeitgeist right in the moment, rather than retroactively. This song sort of sounds as though it were written years later about the 60s counterculture, but actually captures the exact cultural moment in which it was produced, as a balm for residents of Monterey who were uneasy about the prospect of being overrun by hippies during the soon-to-be iconic festival that would bear their city’s name. Above all, though, the vocal stylings are gorgeous. Sweet mustache, too.