Writers on Writers (an almost apolitical issue) - Issue #4

This week, Jason and Fitz write about two authors who shaped their ambitions (and perhaps their styles) as writers, David Foster Wallace and John Updike.

Jason here. Despite — or perhaps because of — the avalanche of important/terrifying/exasperating news developments over the past week or so, I needed a break from writing about politics. As I tried to come up with a topic that didn’t involve my highly-opinionated take on the election and/or the Culture Wars, it occurred to me that it’s been almost exactly a decade and a half since my current career as a professor and writer began to take shape. And I have always felt that that beginning was molded by my discovery of David Foster Wallace’s first essay collection. There is no argument or important takeaway within this article. It is, quite simply, a tribute, an appreciation for an author whose style has (and I’m sure I’m flattering myself here) seeped inextricably into my own.

Upon reading my essay, Fitz dug up and updated a piece he wrote about the influence of John Updike on his own writing life, and, with some critical distance, he wrestles with Updike’s legacy.

After the essays, check out the “What We’re Listening To” and “What We’re Reading” sections.

The Infinitely Perfect Non-Fiction of David Foster Wallace

by Jason Clemence

Just about 15 years ago, I took my first big step toward a career based in writing. Wallace was right there with me.

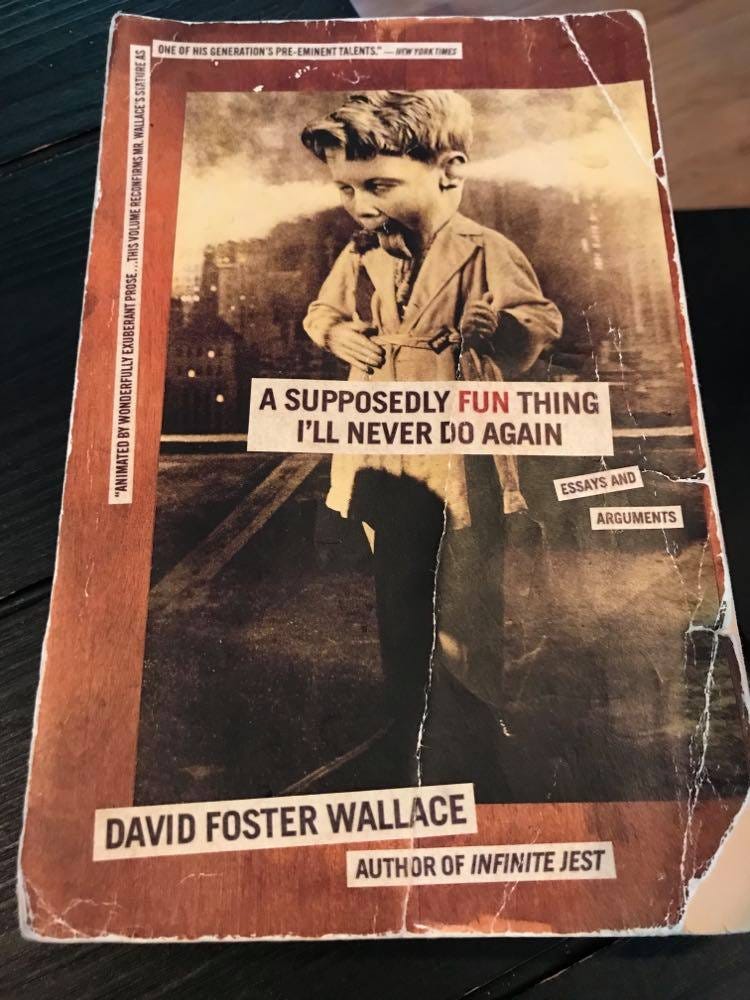

Almost exactly fifteen years ago, when I moved from western Massachusetts to Burlington, Vermont, to begin a two-year Masters program in English and, somewhat inexplicably, to be entrusted with teaching two sections of an undergraduate writing class at UVM, I brought with me a just-barely-started copy of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, David Foster Wallace’s 1997 start-to-finish awesome collection of essays. I’d only heard of Wallace at that point because of an article in The Onion that poked fun at his tendency to overthink and his willingness to devote as many words as necessary — page-long sentences and footnotes and the kitchen sink, if necessary — to expressing that overthinking.

That move to Vermont was one of the most consequential decisions of my life so far, matched only by having kids and a certain early October trip in 2010 to the local Irish pub, where I met my wife.

In 2005, I had been working as a bartender and waiter at a brewery/restaurant in Amherst for two years; I had stayed in the Pioneer Valley only because I wasn’t quite ready to give up on the college life I had loved so much, and because my girlfriend was still a student at Smith—though that relationship only lasted until maybe March of the first year. I was living in a slummy apartment a few blocks from downtown Northampton, overindulging in everything, perpetually unhappy, fantasizing about a creative life and career, but having little idea of how to begin one. I had a BA in English, knew I was a pretty okay writer, but had no idea how to even make writing a fulfilling activity, much less a career. I channeled what creativity I had into recording a singer-songwriterish demo CD full of simple chord changes and hopelessly banal lyrics, and played some open mics, usually to a justifiably disinterested crowd of a dozen or so.

Wallace didn’t make much of an impression on me while I was still in western Mass. I got about halfway into the second essay of the collection, “E Unibus Pluram,” and then tossed the book aside to begin packing boxes for my move north.

I arrived in Vermont feeling entirely different about myself as a writer. Not because I’d written anything worth reading, mind you, but because in Burlington I had to write. And think about writing. And teach others to write better. And then give them feedback on that writing. It was my job now, just as much as pouring draft beers and shaking overpriced martinis and throwing down baskets of chicken wings and saying “We don’t have Bud, we make our own beer here” had been for the previous two years.

It was as though something in my brain reached a tipping point somewhere along Interstate 91. Or, more realistically, perhaps, it was as though the sudden structure and demands of being in grad school and having a teaching fellowship (again, how I was deemed qualified for that fellowship at the time, I’ll never understand) snapped me into shape. A thing that I previously wanted to do, but didn’t know how to begin doing, became a fundamental facet of my identity.

In the lazy days between moving into my apartment and the beginning of the semester, I turned back to A Supposedly Fun Thing. The first piece I read — on my faux-leather couch in a students-only condo complex that smelled of fresh carpet and spackle and was many orders of magnitude nicer than the crumbling apartment I had moved out of a few days prior — was the State Fair Essay, officially (and ludicrously) titled “Getting Away From Already Pretty Much Being Away From It All.” It’s a long first-person narrative in which Wallace wanders more or less aimlessly around the Illinois State Fair and writes about what he sees in a detached, anthropological style that is somehow both casual and dismissive as well as disciplined and stylistically brilliant.

Choose any sentence from that essay, literally any one sentence, and I bet it will be fabulous, in and of itself. Toward the end of the essay, he describes his decision to finally go on a ride, noting that it would be “journalistically irresponsible” to write about them without experiencing at least one. Because he is entirely uninterested in the “Near-Death Experience” rides (a trait he and I have in common), he chooses the “Kiddie Kopter”:

. . . a carousel of miniature Sikorsky prototypes rotating at a sane and dignified clip. The propellers on each helicopter rotate as well. My copter is admittedly a bit snug, even with my knees drawn up to my chest. I get kicked off the ride when the whole machine’s radical tilt reveals that I weigh quite a bit more than the maximum 100 pounds, and I have to say that both the carny in charge and the kids on the ride were unnecessarily snide about the whole thing.

I find Wallace’s work incredibly difficult to teach. I’ve tried and failed a couple of times, with this essay and others, to impart his singular brilliance to my students, most of whom have not been impressed. And that’s understandable, because there is no obvious reason to call this excerpt, or many of his other observations, “brilliant.” There’s definitely something here about his sardonic wide-eyed disbelief that a hulking 30-something man with a ponytail would be scorned for going on a ride meant for children. But being sardonic isn’t necessarily a trait reserved for literary wunderkinds. There’s something else, something unexplainable, something about this particular excerpt’s role in the larger context of Wallace’s minutely-calibrated sense of voice, tone, and observational power that makes those 86 words not just funny or amusing, but genius.

So anyway, I read that essay in Vermont and something about the world around me was suddenly different. Something clicked. I read all 65 pages in an afternoon, and I was hooked. His personality, his ability to explicate, his playfulness, his philosophical tangents, his vulnerability, his imposing vocabulary, even his descriptive randomness, resonated in almost everything I wrote for the next several years. At least in terms of writerly aspirations, I wanted to be him.

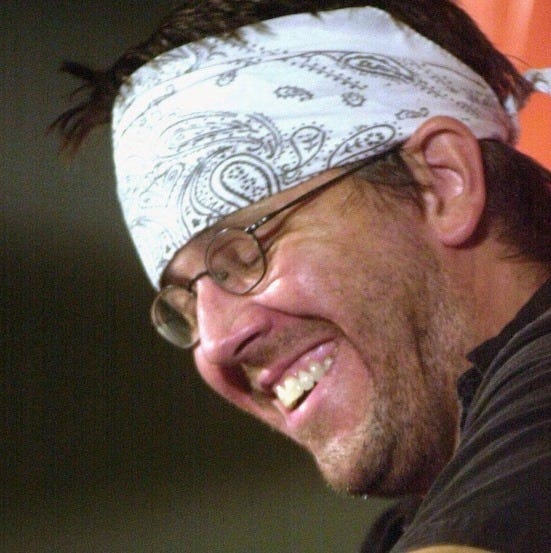

But not in every way, as it turns out. When Wallace hanged himself in fall 2008, the stories of his gargantuan struggles with depression and anxiety — one of few things that he did not exhaustively reveal about himself in his essays — became, in dribs and drabs, public knowledge. The “tortured genius” is a tired, tired trope, but it seems clear that Wallace was the real deal. By all accounts, he was a frequently miserable man.

And, of course, reassessments of Wallace’s work have not been entirely positive. Infinite Jest, once considered a masterpiece of postmodernism, a continuation and refinement of writers like Gaddis and Pynchon, has gradually come to be seen in many circles as a monument of self-indulgence and privileged cluelessness; notice it’s number one ranking in this sort-of-but-not-really-joking list. And indeed, my deep and abiding appreciation of Wallace’s work simply does not extend to his fiction. I’ve tried, but the only work I’ve gotten through is the exhaustingly-detailed “Mister Squishy,” a mildly-amusing slog in the middle of his collection Oblivion that, if nothing else, satisfyingly makes the case that it’s possible to be nerdy and obsessive about just about any topic. I tried to read Infinite Jest twice, and never made it past page 400 of 1,079. The second time, I came down with pneumonia somewhere in the 300s and endured a night of fever dreams that heavily featured images and characters from the novel’s dense and tangled paragraphs. At one point, I fell out of bed and got a black eye from my nightstand. I haven’t picked up Infinite Jest since, and I still churlishly blame it for — or, at least, associate it with — that illness and injury.

But his non-fiction? I’ll read it any time. It’s like talking with an old friend, one whose language bubbles with inspirational energy even when the subject matter is mundane. Wallace’s own old friend, the novelist Jonathan Franzen, put it perfectly:

[David] had the most commanding and exciting and inventive rhetorical virtuosity of any writer alive. Way out at word number 70 or 100 or 140 in a sentence deep into a three page paragraph of macabre humor or fabulously reticulated self-consciousness, you could smell the ozone from the crackling precision of sentence structure, his effortless and pitch-perfect shifting among levels of high, low, middle, technical, hipster, nerdy, philosophical, vernacular, vaudevillian, hortatory, tough-guy, brokenhearted, lyrical diction. Those sentences and those pages, when he was able to be producing them, were as true and safe and happy a home as any he had.

Fifteen years ago, my status as a writer shifted from aspirational to actual. David Foster Wallace’s work was not the only reason that this happened, but it was integral. And it taught me that all of the different modalities and intangibles of writing — the argumentative, the analytical, the reflective, the evaluative, the entertaining, the personal, the impersonal, humor, sadness, exuberance, and virtuosity — not only could, but often should coexist in the same book, the same essay, the same paragraph, the same sentence, or even the same word.

Remembering and Reconciling with John Updike

by Jonathan D. Fitzgerald

Many years ago, when my wife and I were living in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts, I had this habit of staring at old men. Each morning as I drove through town on my way to work my head turned in the direction of every white haired, well dressed older gentleman who happened to be walking around town. I couldn’t help myself. John Updike lived less than a mile from our apartment and I wanted to meet him.

I first read John Updike when I was a freshman in high school. The often anthologized “A&P” was the story. I like to tell people that it is the story that made me want to write stories. It appealed to me then because it was immediately relatable. I was working at a grocery store called Johnny’s Foodmaster, my first job. And although I wasn’t a cashier as the main character in the story is, I did often use my bagging station as a perch from which to steal glimpses of the few young girls that would come in to pick up milk or eggs for their mothers. And I certainly shared the main characters’ tendency toward delusions of grandeur.

My appreciation for that story matured as I did, and it served as a gateway into the rest of Updike’s writing. I can very nearly trace decisions in my life that led toward my development as a writer to many of Updike’s stories and essays that I encountered over the years. I decided that short fiction was my genre of choice, for example, when I read “Leaves” from 1967’s The Music School. Later, after reading Hugging the Shore, first published in 1983, I turned my attention to non-fiction. Since those early days a plethora of other influences have arisen as I worked to find my own voice, and my views on Updike’s writing—turns out, it’s rife with the misogyny and narcissism—have been tamped down, but I can’t deny that initial connection to Updike’s writing.

It wasn’t until I was a sophomore in college that I learned of our geographic connection. There it was widely known that the same John Updike that we read in our literature anthologies was a neighbor of the school. It was also known that despite his close proximity, Mr. Updike would not be visiting our English classes anytime soon. The explanation however was less clear. There were rumors of a disagreement between a member of the faculty, or administration, and Updike. Whatever the reason, though we still read his stories in literature and creative writing courses, he would never be speaking in a classroom or at convocation. I don’t have any confirmation that this rumor is true aside from the fact that in my time as a student, and later as an adjunct professor, John Updike never visited campus.

Of course there are many other Updike stories floating around the North Shore of Boston. Another such account has one of my former English professors rear-ending John Updike’s car somewhere in Beverly. In the rendition I heard, an interesting conversation sprung up between them and they discussed writing over the exchanging of insurance information.

I have a friend of a friend who did landscaping at the Updike home and actually saw his Pulitzer Prize and another friend who used to deliver pizzas to the Updike’s. The owner of a local used book store, Manchester by the Book, explained to me one day as I was browsing that every so often he has to drive over to Updike’s house to pick up the books that he chooses not to read of those that are sent to his house with the hope that he will review them. Even while workshopping this essay, a good friend and fellow writer prefaced his critique with a story about meeting Updike in The Book Shop, a small bookstore here in Beverly Farms. That’s the same shop from which my mother-in-law bought me a signed copy of Updike’s 2006 novel Terrorist; he apparently signs all of the hard cover editions of his books that they sell there.

And yet I never saw him around town, let alone met him. From my office in our old apartment I could look out the window across to the library where his name is inscribed above the windows among other literary Farms’ residents. I would often peer out that same window down onto the street to see if he happened to be window shopping below, but to no avail.

So why did I want so badly to meet John Updike? What would I have said to him?

It’s not as if I was an adoring fan who wanted an autograph; anyway, as I mentioned, I already have one. I didn’t necessarily have a manuscript that I wanted him to read. (Though I’m sure I could have thrown one together pretty quickly, if asked.) I didn’t want to approach John Updike as a fan, or an admirer, and I was certainly not a colleague. I wanted to meet him as a skeptic; a young person who didn’t quite believe that the writing life can actually be a life. I wanted to meet him as someone who knows plenty of books but very few authors. I wanted to know how the words that I had spent my young life storing inside me could have originated inside someone else, another human being.

When I sit down to write I have the sense that although I am alone physically, I am also in great company in that I am surrounded by a chorus of writers’ words rising up from everywhere, including from inside. I try to keep this connection before me at all times so that I don’t feel like I’m on my own island, writing my own thoughts, to be shared with no one beside me. But I need a physical reminder of this community as well. That’s why scattered all over my desk are my favorite books from the writers I rely on the most, always within arms’ reach should I need encouragement or inspiration or simply diversion.

But at some point, a writer realizes that more community than this is necessary, that while the words still live inside the computer, on the white plain that is made to look like real, physical paper, they don’t actually exist yet. And it’s hard to make the connection between the words in the books around me, the physical books, and their origins, potentially on similar digital “paper.” Harder to imagine still is the connection between these words, existing in invisible space, the words between book covers, and the woman or man who has watched the process progress from bodiless words to physical pages. And I used to find it nearly impossible to connect the names on the spines of the books on the shelf next to me with the person pictured on the dust cover and just as hard to connect that two-dimensional person in black and white with the real, three-dimensional full color, living, breathing human being.

But I wanted to meet that human being. I wanted to know someone who knows that these words can actually become physical things. And, back when we were living in the same town, I had come to believe that John Updike could have helped me make this connection. I believed this because I know that he too struggled with this disconnect. In a short piece called “Updike and I” found in the last section of More Matters he concocts a monologue by “I” about the other, “Updike.” It is written in the model of Jorge Luis Borges’ essay “Borges and I” published in 1964. Updike’s piece is enlightening not only because it actually describes how “Updike and I,” both, react to meeting an admirer, but it illuminates the space between writer and real person. Even John Updike felt some disconnect between the writer of the same name. Even he couldn’t quite see how the person who spends time in front of the word processor can possibly be the same person who reads the newspaper with breakfast in the morning. It is as if the words that one takes in and the words that one sends out pass each other somewhere inside of a person but the two identities rarely meet.

Still, this small comfort, this modest assurance that even established authors question their relationship to their own writing and that of others comes from the same place it always has, words on a page. I know from reading Updike that he, the man, could never have offered me that same comfort in person. He probably would have felt as awkward as I, eyes dashing to corners of the room falling on anything inanimate, anything safe. Because the inanimate objects, the heavy books, and the light ones too, are the things we trust the most, even when the living beings are what we want the books to help us understand.

And help us to understand, they do. In fact, as I matured as a writer and reader, as I began to better understand Updike and his characters, it became impossible to miss his many flaws. And, of course, his work and reputation were already experiencing a critical reconsideration before he died in 2009. In a scathing review of Updike’s novel Toward the End of Time, David Foster Wallace labeled him and his contemporaries the “Great Male Narcissists,” or GMNs. Updike, Wallace writes, was “both chronicler and voice of probably the single most self-absorbed generation since Louis XIV.” Wallace acknowledges that he’s a fan of Updike—particularly, “the sheer gorgeousness of his descriptive prose.” And yet, he calls out Updike’s “radical self-absorption,” and the uncritical celebration thereof. And beyond the self-absorption, Updike’s novels are sex-obsessed, misogynistic, and just dripping with the kind of white male privilege that has proven to be so toxic in contemporary American life.

This might all amount to Updike being cancelled, I suppose, if natural causes hadn’t cancelled him over a decade ago (see Bill Burr’s recent monologue on SNL for a funny bit on how God cancelled John Wayne 40 years ago). But let’s not cancel. Canceling an author would be the same as banning their books, and banning books is just one step away from burning them. Rather, I find that the more distasteful I find Updike now, the closer I actually want to look. I don’t want to turn away from what repulses me; I want to better understand it. After all, Updike was the chronicler and voice of the most self-absorbed generation, the generation that gave us the Great Male Narcissist-in-Chief; reading Updike might help us understand how we got here. Besides, if you’re not reading critically, are you even reading?

Anyway, I never did meet Updike. Not on the street, nor in the library, the bookstore nor the beach. So, I can’t say what it is like to shake hands with the man who wrote the stories and essays that proved so formative in my youth. Still, even as I’ve come to laud Updike less and to see him as the flawed human he was, just knowing that he existed, and for a time, in such proximity to where I lived still comforts and empowers me to offer back the little I can. In this case it is these words, in black and white, inanimate as they may be, as an attempt at reconciliation, of understanding.

What We’re Listening To:

Jason: I’ve been on a huge East Coast “boom bap”-style hip hop kick lately. Notorious BIG, Mos Def, Nas, and Gang Starr have been in frequent rotation all summer. But this past week, I’ve gone back to a comfortable old favorite: Digable Planets. Their first record is a masterpiece, a desert island album for me. Here they are, waaaay back in 1993, making their debut appearance on Letterman. It’s an awesome performance of one of their best songs. Jump to 1:10 to skip Letterman’s banter, and don’t forget to take a moment to remember the days when CDs came packaged in 3 square feet of cardboard…

Fitz: While the 90s hip-hop that Jason has been listening to is the music of my youth (his Digable Planets pick resurrected a cherished memory of my dad buying me a Digable Planets cassingle back in the day), I’ve been doing a ton of grading lately and, for me, grading means instrumental music. So I’ve been listening, almost exclusively, to classical pianists including Víkingur Ólafsson’s “Philip Glass: Piano Works”, Martha Argerich’s “Chopin: The Legendary 1965 Recording”, and Lang Lang’s “Bach: Goldberg Variations.” Here’s a clip of Lang Lang playing recently on Colbert:

What We’re Reading:

Jason: It only seems appropriate to list my top 5 favorite DFW essays. I almost wrote the above essay as a “listicle,” with a detailed analysis of each of my five picks, but thankfully suppressed the urge. So here are the picks, sans commentary, each followed by the collection it appears in:

“Getting Away From Already Pretty Much Being Away From It All” (A Supposedly Fun Thing)

“A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” (A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again)

“Federer, Both Flesh and Not” (Both Flesh and Not)

“How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart” (Consider the Lobster)

“Twenty-Four Word Notes” (Both Flesh and Not)

Fitz: Walter Kirn is an author whose work I admire quite a lot and he’s also a person I follow on Twitter. In an exchange there a few weeks ago, I mentioned that I was thinking of starting a newsletter for all the reasons I stated back in Issue #1, and he encouraged me to do so. So, thanks Walter. Anyway, back in March he tweeted:

So, I took his advice and have been reading (and really enjoying) Mission to America.