This week, we welcome Jon Busch back to In Progress!

“The rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated.”

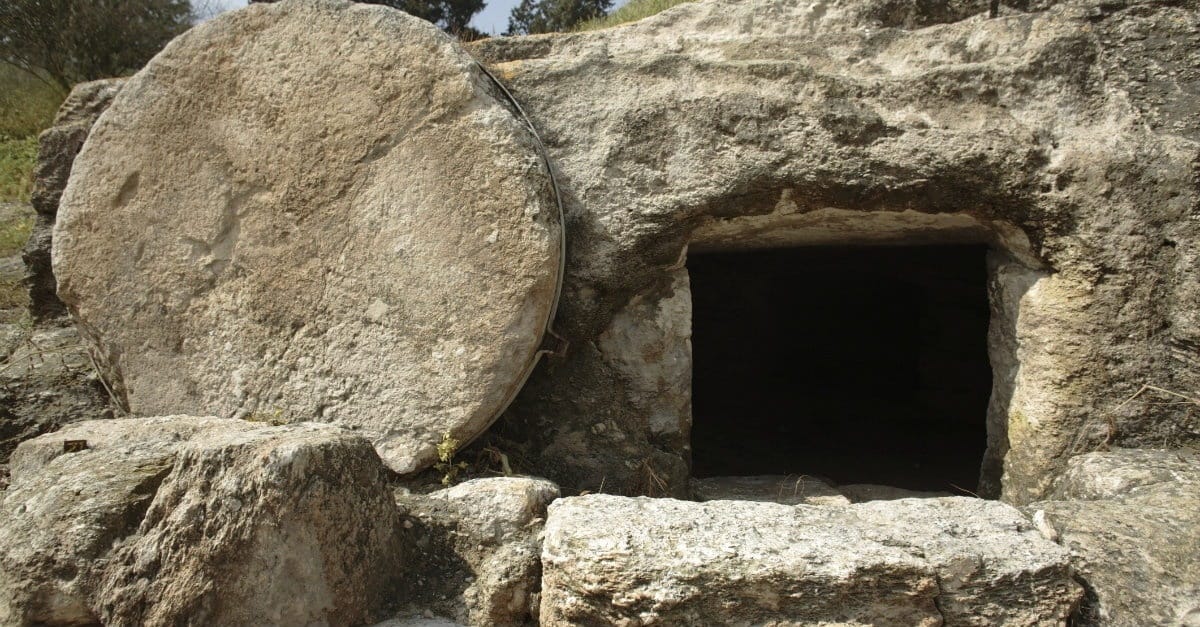

I guess Mark Twain never really delivered this witty quip, but I always thought it would’ve been hilarious if Jesus had said it to his disciples following that first Easter.1

I too am back from the dead, so to speak, after three years spent in a kind of writing tomb. My post-Covid years got pretty dark, to be perfectly honest. I’ll spare you the gory details (for now), suffice it to say that I’ve gone through a rather embarrassingly stereotypical mid-life crisis over these last few years, and my hope is that you are meeting me now as I emerge on the other side of it. Fingers crossed; prayers welcome.

I can report that I did not have an affair or buy a motorcycle. I did something even more desperate: enrolled in seminary!

Okay, I’m auditing one course. But it’s quite a doozy. It’s called “Cultural Apologetics: Morality, Art, and Story.” I thought we would be analyzing contemporary art and media through a spiritual lens, but it’s more about the decline of Christianity in Western Culture from the days of Marx and Nietzsche to the present.

The first book we read was Death in the City by the famous Evangelical author and pastor, Francis Schaeffer. I was thrown by his opening sentence: “We live in a post-Christian world.”

From that stark assessment, Schaeffer goes on to bemoan the moral breakdown of society and the postmodern spirit of relativism he sees infecting art, culture, and even the Church, drawing people away from God and toward an amoral secularism. The class pretty much operates on the premise that Schaeffer was correct and that things have only gotten worse since the book was published in 1968 (Imagine if Schaeffer had seen Woodstock!).

I have supposedly lived my entire life in this “post-Christian world.” And yet, here I am, a Christian. Apparently, nearly 2.5 billion other Christians inhabit this planet as we speak, which raises some doubts for me about the thesis.

180 years after Marx castigated religion as the opiate of the people, 150 years after Nietzsche declared that “God is dead,” and more than 50 years after Francis Schaeffer claimed that “we live in a post-Christian world,” it seems to me that Jesus persists in his stubborn refusal to be buried. The cross we contemplated this past Easter weekend was only the first of many unsuccessful attempts to kill him.

Christ has a whack-a-mole-like quality. Various competitors step up to bash him down, but he just pops up somewhere else. Seemingly effective whacking might result in some reward from our cultural machine, little paper tickets one might cash in for various, colorful yet ultimately worthless items. But the mole is not dead. He can never be truly ‘whacked.’ He lurks interminably beneath the whole apparatus.

He’s continued to lurk beneath my own life also.

After being turned off by what I saw as Evangelical Christianity’s unholy alliance with the Republican Party and conservative media, I embarked on what could be categorized as a pretty typical “deconstruction” journey from my 20s onward. With Catholic priests and Southern Baptist ministers alike being exposed as serial abusers, conservative discourse taking on an evermore seething and sneering tone, and finally the blatant hypocrisy of the Christian Right’s embrace of Trump (see Fitz’s piece from last week), it wasn’t hard to keep my distance.

One command I could never quite let go of was to “remember the Sabbath” – it is one of the big ten, after all – and so I continued attending church religiously, albeit at what I would describe as the theologically loosey-goosey Episcopal Church. I was fine with this because I didn’t know what I believed anymore.

I let myself be challenged by any and every idea I came across, and was willing to let the faith go once and for all should I find a suitable alternative. Spiritually, I wanted to dive headlong into the fiery furnace, as it were. If any remaining faith emerged from the inferno, I wanted it to be one free from both fear and intellectual compromise.

I am pleased to report that my faith was not entirely consumed. What survived were just a few basic but important ideas: forgiveness, belonging, redemption.

One idea I couldn’t shake is the sense that I need some kind of cosmic forgiveness. Yes, I’m always trying to become a kinder, better human being. But there are actions I can’t take back, words I can’t unsay, wrongs I can’t right, things known and unknown, done and left undone.

In his book, Unapologetic, Francis Spufford cleverly and provocatively rebrands “sin” as “the human propensity to fuck things up.” I resonate with this concept deeply, as I think most of us can. It evokes less offenses against a mysterious, other-worldly God or failures of personal purity and asks us instead to reflect on how we’ve let people down or failed to love people properly, including ourselves.

Most of us can recollect, often with a hot rush of regret, a hurtful comment, a joke made in poor taste, a self-serving lie, a time we bullied or mocked someone, rejected someone as inferior, betrayed a friend or romantic partner, spread a nasty rumor, or lashed out in anger. Such memories can still keep me up at night, and I find the prospect of this slate of shameful offenses being wiped clean someday immensely appealing.

Another author who influenced me a lot over the years is the Anglican theologian N.T. Wright. He challenges his audience to think of heaven not as some alternate dimension we are transported to when we die, but as a kind of redeemed version of the Earth we currently inhabit. Invoking the Lord’s Prayer, Wright asks what it would be like for God’s Kingdom to actually come, for God’s will to actually be done on Earth as it is in Heaven.

I think we get little glimpses of Heaven and Hell all the time. The sense of belonging we get with a group of cherished, old friends, the sense of transcendence we feel when we look out at the ocean or hear a beautiful melody, etc. are heavenly experiences. At the same time, I can’t imagine any tortures to be perpetrated by the devils of hell that have not already been accomplished here on Earth. War, starvation, abuse… the horror is ubiquitous and unending if we can stomach looking at it.

Heaven being the former without the latter is the first vision of the place I could really accept.2

All to say that through doubt, anger, openness, and exploration, I could never quite shake the basic concept of Christ. And despite assaults from Marx, Nietzsche, Hitchens, Dawkins, or Harris, it seems I’m far from alone in this supposedly ‘post-Christian’ world.

There’s something uniquely compelling about this Jesus character that he could persist through so many cultures for so many generations all around the world. And believe me, it’s not what many of the louder voices in our culture say it is.3 I think that’s what I’m trying to explore by taking seminary classes, and I’d like to explore it here on in Progress as well. I hope you’ll come along for the ride!

I like to think he did and it was nixed by the Council of Rome when they were compiling the New Testament.

More on this in a future post!

More on this to come, I hope, as well!

Love this! Thank you!!!

Great to read this new installment, and glad to hear of the new pursuit, Jon.

I guess I had a somewhat similar trajectory, some time back. Although I hadn't been going to church since my teens, I was never, I guess an unbeliever (I just didn't like church). It wasn't for lack of trying, as I read all the "New Atheists" and then some...Dennett, Dawkins, Harris, et al. I wanted to read all the arguments and understand their "belief."

It just never took. I could comprehend the reasoning, but never "felt" it. And that's the conclusion I came to: you can reason about faith (and I do believe hardline atheism is a faith, rather than just a bundle of provisional "credences," in materialist talk), but you can't reason your way to faith.

It really is, in the end, a question of the heart (not the literal organ, of course, but its spiritual proxy). Faith is immediately apprehended, not through the brain, but through the heart (or as the Desert Fathers might say, the "intellect," the seat of the soul). Mistranslation or no, the Kingdom of Heaven (or its opposite) indeed is within.

Look forward to reading more.