Last week, my kids’ school conducted a “silent safety drill,” which is a euphemism for “active shooter drill.” Their teachers did a great job of explaining what was happening in an age-appropriate way, but my daughter, who is in fifth grade, had questions. I chose to be honest.

Why do we have to do this?

Because all around our country, for the past couple of decades, people with guns have gone into schools to kill kids.

Does this happen in every country?

No, not really. Our country is uniquely broken in this way.

We went on to talk about the proliferation of guns in the U.S., about hunting and recreational shooting. About how to interpret the Second Amendment and how hard it has been to make meaningful change. About brokenness.

I told her: we are broken—as a country, I mean—and the effects are increasingly difficult to ignore.

We can see the brokenness in so many aspects of life in America. I’ve been heartened that Jonathan Haidt’s new book The Anxious Generation, which I’ve mentioned here, is impacting the national conversation about the well-documented mental health crisis among children and teens. Haidt blames the double-edged sword of overprotecting kids in the real world and not doing enough to protect them in (and from) digital spaces. Critics have pointed out that there’s never just one reason why mental health might be impacted, and they’re right of course, but that doesn’t invalidate Haidt’s claims so much as illustrate how big the problem is.

We’re broken.

I’ve been thinking about the causes of our brokenness, too. Lately, it occurs to me that many of the frequently identified culprits—social media among them—are actually symptoms rather than causes. That is, for causes we should look further upstream.

I’m thinking about bad trees bearing bad fruit.

I’m thinking about how our values dictate our behavior.

I’m thinking we put too much value on ease.

In The Chaos Machine, journalist Max Fisher writes about how, when the internet became our lingua franca, values that were intrinsic to the culture of early Silicon Valley innovators became the values we all share. Fisher identifies “an ideology that said more time online would create happier and freer souls” and “a strain of Silicon Valley capitalism that empowers a contrarian, brash, almost millenarian engineering subculture.” Fisher is right, and his thesis goes a long way to explaining how social media has upended our society. But also embedded in this Silicon Valley ethos is an emphasis on ease—convenience, seamlessness, intuitiveness, optimization—that the general population has subconsciously adopted.

In some ways, this is not new; as long as humans have been making things, the primary purpose of invention has been to make life easier. There’s nothing wrong with that. But somewhere along the way, as our devices moved from being mere tools to being extensions of ourselves1, the notion that we can and should optimize all aspects of our lives for ease has taken primacy of place. This is a theory I’m workshopping. I’m calling it “The Valorization of Ease.”

This reordering of priorities touches many aspects of modern life, and in future issues, I intend to explore the ways in which this phenomenon impacts religion, politics, education, and so on. But here, to illustrate the point, I want to think about how the valorization of ease impacts art and culture.

There’s a notion, attributed to William Morris, that “you can’t have art without resistance in the material.”2 Not surprisingly, the context in which Morris is purported to have made this remark was a kind anti-technology screed, though in this case the technology was the typewriter. Here’s more of the quote: “The minute you make the executive part of the work too easy, the less thought there is in the result. And you can’t have art without resistance in the material. No! The very slowness with which the pen or the brush moves over the paper, or the graver goes through the wood, has its value.” There is value in slowness, in resistance, in challenge. A little suffering can be good for art-making.

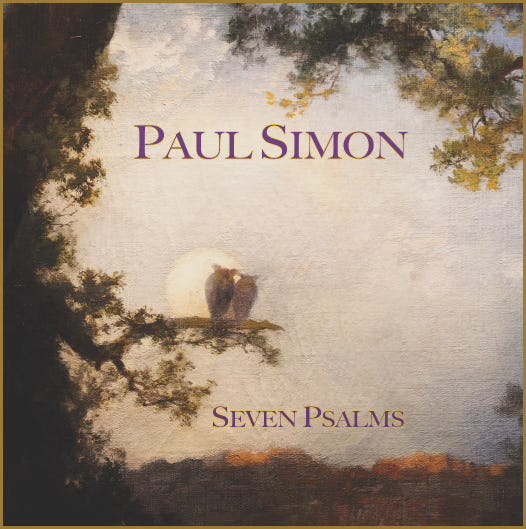

Of course, the notion that one should suffer for their art is a cliché, but I thought of it recently as I was watching an excellent documentary: In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon. I love Paul Simon. I own all his records, I’ve read his biography, and so of course I subscribed—temporarily—to MGM+ so I could watch the doc. And I was not disappointed. It traces the contours of Simon’s decades-long career, while simultaneously documenting the making of his latest album Seven Psalms.

During the process of making the record, Simon, who is 82-years-old, lost hearing in one ear. For a sound-obsessed musician like Simon, this was devastating, but, in the film, he takes it in stride, hypothesizing that perhaps this suffering was necessary to the process of making the album. Simon says in the documentary, as he has said elsewhere, that the idea for Seven Psalms came to him in a dream. He heard a voice telling him, you’re making a record called Seven Psalms. Along with the dream came a lovely little guitar riff. That was the easy part, the rest was struggle.

To be honest, listening to the record for the first time was a bit of a struggle, too. While Simon’s work has long pushed listeners outside of the comfort zone of typical pop music, Seven Psalms pushes harder and further. It is not a typical album comprised of individual tracks; rather, it is one long song with several distinct movements. While the movements are different enough to be individual songs, you can’t skip forward or back through them. Listening to the album is committing to one 33-minute track. Likewise, Simon eschews the traditional pop song structure. Don’t expect verse-chorus-verse-chorus-break-chorus here. It’s more like stream-of-consciousness poetry set to music.

All of this is to say that upon first listen—in the background while trying to work—I couldn’t connect to Seven Psalms. It wasn’t until watching the documentary, and seeing how Simon struggled to make the record, that I thought, maybe a little struggle on the part of the listener was warranted as well. I bought the album on vinyl and sat with it. And listened. And I was moved. Truly. In a way that music hasn’t moved me in some time.

Of course, Paul Simon, an established musician with devoted fans, can release a record like this and expect that his loyal listeners will work through it. Or not. And I have to imagine that, to him, it doesn’t much matter whether we connect with it or not. But this notion does not fit in the current pop culture landscape, nor, as I’m arguing, does it fit anywhere within a culture that valorizes ease. Read reviews of Taylor Swift’s latest album and you’ll see some astute critics suggesting that perhaps her musical collaboration with producer Jack Antonoff has grown stale since so much of Swift’s latest album, The Tortured Poet Society, sounds like she simply put songs from her last few albums into a blender. But check the sales and streams and it’s clear that familiar songs blended together is precisely what the people want.

Arguably, pop music is not the place to look for challenging art. But also, the way that what is popular has become monolithic speaks to the valorization of ease. It’s so easy to consume pop music that everything else falls by the wayside. Listening to pop music today doesn’t require seeking and finding. It is spoon-fed through the algorithmic streaming services that we outsourced our taste to because hitting “shuffle” on a familiar genre is so much easier than developing personal taste. There used to be some resistance in the materials when it came to appreciating music; now, the machine has made the way smooth.

Great art challenges us. It asks something of us, a kind of tribute to the artist who sacrificed something of themselves in the making. Easy art, on the other hand, doesn’t challenge us, doesn’t help us grow. Some might argue that this is a relatively trivial arena in which to begin to test my theory, but I don’t think so. I think art matters. But beyond art, in so many aspects of life in the United States3, it feels as if we have plateaued, if not regressed. One could point to a number of potential causes, but follow those causes upstream and, I believe, you’ll find the valorization of ease.

Hat tip to Marshall McLuhan

I was introduced to this quote and William Morris in the context of Digital Humanities by Bethanie Noviskie, in her essay “Resistance in the Materials,” published in Debates in Digital Humanities 2016

I’ll explore these in future issues.